Smallpox in the Sea Islands: Clara Barton in South Carolina

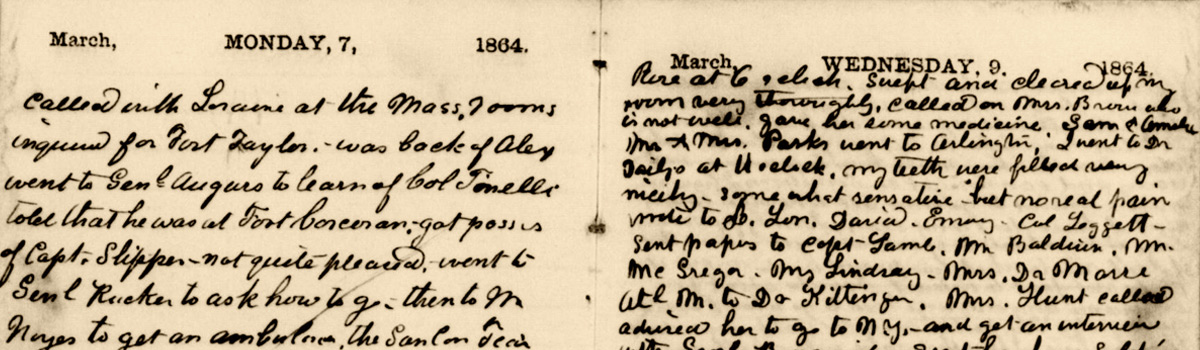

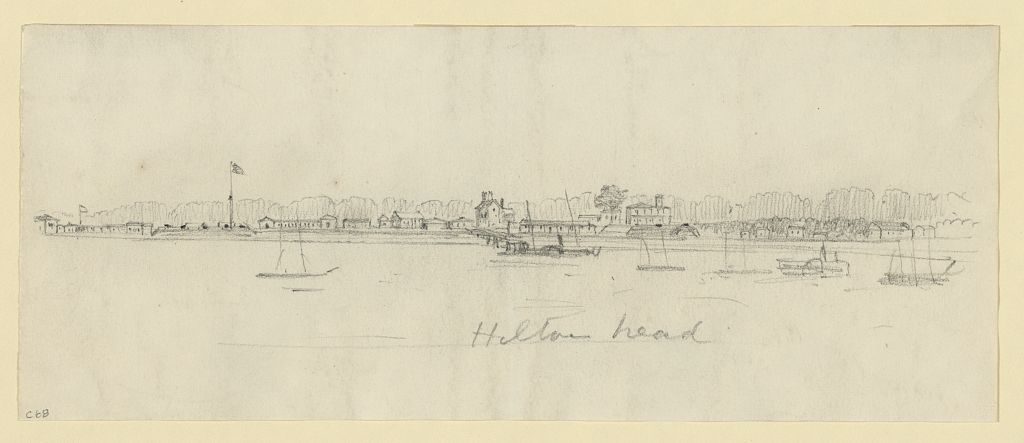

At three o’clock one Tuesday afternoon, Clara Barton sailed into Hilton Head, South Carolina with a bang. She was going there to nurse Union Army soldiers and inspect hospital boats. Just as her ship pulled up to the dock on April 7, 1863, nine federal ironclads launched an attack on Forts Sumter and Moultrie as part of Union efforts to recapture Charleston. Confederates battered Union vessels with 2209 artillery shells, federal boats responded with 154 more of their own before limping back out to sea, and Barton feared she would “sink through the deck” from all the explosions. “I am no fatalist,” she confided in her diary that night, “but it is so singular.”[1]

Sketch of Hilton Head during the Civil War Courtesy of the Library of Congress

Clara Barton’s “singular” arrival heralded the beginning of what would become her nine-month stay in the Sea Islands. While she was there, African American soldiers of the Massachusetts 54th Infantry would storm Battery Wagner as part of the same campaign that began at the moment of her arrival at the Hilton Head dock. She was still nursing survivors of that July attack when Wagner finally fell in September. Meanwhile, small pox devastated former slaves living under the protection of the Union Army throughout the Sea Islands, and the indomitable Miss Barton—used to marching in, assessing a problem, and solving it—could do nothing to alleviate that suffering. Or rather, she could do nothing by herself.

Nineteenth-century Americans were no strangers to smallpox. Clara herself had survived the disease in her youth, which made her immune for the rest of her life. Many more were not so lucky, especially under wartime’s crowded and unsanitary conditions, which facilitated the spread of the dreaded disease and weakened victims’ ability to fight it. The Union Army reported nearly 19,000 cases of smallpox among Union soldiers, with mortality rates at roughly 23 percent for white soldiers and 35 percent for African American soldiers.[2]

Portrait of Clara Barton

Former slaves were even more vulnerable. Aware that their bondage rested at the heart of the war, enslaved men and women fled to the Union Army wherever it infiltrated the Confederacy and helped it to fight their former owners, sometimes by enlisting if they were men, but also by spying, nursing, growing crops, and performing every imaginable type of labor necessary to keep a large army battle-ready. Roughly 48,000 formerly enslaved men, women, and children took refuge with Union forces in the Department of the South, which ran through the coastal regions of South Carolina and Georgia into the very northern tip of Florida, and whose core consisted of the Sea Islands where Clara Barton arrived in April 1863.[3] They, like refugees who encamped with the army throughout the occupied Confederacy, found a route out of slavery, but they also encountered a host of dangers. Crowded, located in perilous war zones, and perennially short of everything (including vaccine), camps created the perfect conditions for the spread of disease, including smallpox. Smallpox cases appeared in Washington, DC in 1862, and spread throughout the theaters of war.[4] Outbreaks sickened and killed thousands, and they worsened other problems like sanitation and even clothing shortages, because garments touched by the infected had to be burned to stem contagion.

Smallpox beat Barton to the Sea Islands. By the spring of 1863, several cases had already broken out among Union troops, including the African American men of the 54th Massachusetts Infantry.[5] The disease quickly spread among the formerly enslaved.[6]

As the disease stalked communities of freedpeople, Barton’s work with soldiers and hospital boats proved less time-consuming than she expected, and she found herself at loose ends. She befriended Frances Gage, a woman from Ohio who had been active in abolitionist and woman’s rights circles before the war, and who now served as Superintendent of Paris Island. Gage was tireless in her efforts to alleviate suffering among the 500 former slaves there. Her example compelled Barton to examine her own vague, theoretical opposition to the institution of slavery. Amidst the hunger, illness, maltreatment, high mortality, courage, and resolve of men, women, and children who had escaped slavery, Barton realized that polite, detached disdain for the peculiar institution was wholly insufficient to the needs of the times and the needs of people who had endured slavery.

She was moved to act, but she was stymied by a quarantine. The Army was anxious to prevent smallpox from weakening its fighting force. “All communication being closed by military authority,” Barton could not travel between soldiers and freedpeople’s settlements where the disease was present.[7] The formidable Clara Barton, it seemed, could do nothing.

Living within the affected area was a man named Columbus Simonds. Born a slave, Simonds had somehow taught himself to read and write, and when the Union Army came he recognized a chance to carve a path out of slavery. He worked as a servant for Union General David Hunter and he cared for Union General Ormsby Mitchel when the latter contracted yellow fever in Beaufort, South Carolina; Simonds was with Mitchel when he died of the illness in 1862. In 1863, Simonds met and impressed Clara Barton.

In the face of the smallpox epidemic, Clara Barton realized that Columbus Simonds would know exactly what to do. Sick people needed medicine, blankets, tea, nourishing food, and warm, uninfected clothing, especially as autumn began to chill the air. Soliciting and delivering donations for Union soldiers had taught Barton a thing or two about how to gather and distribute supplies. With Simonds’ help, she could apply that expertise to the relief of disease-stricken freedpeople. So she “boxed and sent some tons of clothing and comforts such as I thought them most in need of, landing them silently from little boats up at the mouths of the creeks, into the hands of” Columbus Simonds, confident that she could leave “the proper distribution of them with him.”[8]

Freedmen’s school near the South Carolina sea islands Courtesy of the Library of Congress

Simonds repaid her confidence. Hauling the little boats ashore, he unpacked the boxes and divvied up the supplies to “thousands of old, sick, lame, worn out and helpless men, women and children in a state of utter destitution.” [9] Armed with provisions, freedpeople could better tend to each other, exercising the healing practices long known among them, easing the suffering of those who recovered and those who succumbed, and comforting survivors whose loved ones died.

Smallpox is merciless and it does not always reward heroism. Barton left the Sea Islands at the end of the year, discouraged and depleted by the cruel prevalence of disease and by petty jealousies within the army’s nursing operations. She needed a rest before resuming work in Virginia in the spring of 1864. Plenty of Sea Island freedpeople still died of the awful disease. But among those who were spared, many credited the partnership between Columbus Simonds and Clara Barton. Through Simonds, they sent a gift of “some pretty sea shells from their beautiful beach” to Miss Barton as she recuperated in Washington, D.C.[10]

Footnotes

[1] E. B. Long, Civil War Day by Day, (NY Da Capo, 1971), pp. 335-336; Clara Barton Diary, April 7, 1863, Clara Barton Papers, Reel 1, Library of Congress.

[2] http://www.civilwarmed.org/surgeons-call/small_pox/

[3] Ira Berlin, et. al. Freedom: A Documentary History of Emancipation, 1861-1867, Ser. I, Vols. 1-3; Ser. 2, Vol. 1; and Ser. 3, Vols. 1-2 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1985-2013), especially Ser. 1, vol. 2, p. 77-78. See also Chandra Manning, Troubled Refuge: Struggling for Freedom in the Civil War (New York: Knopf, 2016) and Willie Lee Rose, Rehearsal for Reconstruction: The Port Royal Experiment (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 1964).

[4] Records of the American Freedmen’s Inquiry Commission, Record Group 94 Letters Received by the Office of the Adjutant General (Main Series) 1861-1870 1863-328-0, Microfilm 619 Reel 199-201, National Archives and Records Administration (NARA); Jim Downs, Sick from Freedom: African American Illness and Suffering During the Civil War and Reconstruction (New York: Oxford, 2012), chapter 4.

[5] Susie King Taylor, Reminiscences of My Life in Camp with the 33rd U.S. Colored Troops, Late 1st South Carolina Volunteers, reprint edited by Patricia W. Romero (New York: Markus Wiener Publishers), p. 45

[6] Capt. E. W. Hooper to American Freedmen’s Inquiry Commission, RG 94 Microfilm 619 Reel 200, Frames 392-93, NARA.

[7] Clara Barton to Brown and Duer, editors of American Baptist, March 13, 1864, Clara Barton Papers, Reel 63, Library of Congress.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.

About the Author

Dr. Chandra Manning is an accomplished historian and author of Troubled Refuge and When this Cruel War Was Over. She graduated summa cum laude from Mount Holyoke College in 1993 and received the M.Phil from the National University of Ireland, Galway, in 1995. She took her Ph.D. at Harvard in 2002. Manning has taught history at Pacific Lutheran University in Tacoma, Washington, and currently is a Professor of History at Georgetown University.

Tags: 54th Massachusetts, Chandra Manning, Charleston, Clara Barton, Columbus Simonds, Fort Wagner, Hilton Head, Smallpox Posted in: Uncategorized