Biography

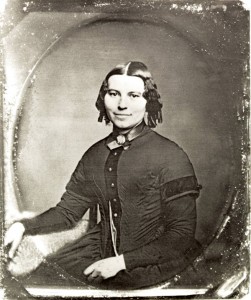

Clara Barton was thirty-nine and on her second career when the Civil War started.

That didn’t stop her from getting involved, making a difference, and ultimately changing the world.

Let’s Back Up a Bit

Clarissa Harlowe Barton was born on Christmas Day (December 25th) 1821 in Massachusetts. The youngest child, with four much older siblings, Clara did not have an easy childhood. Her mother was not kind to her. Her siblings were more parents than playmates. However, Clara’s childhood wasn’t all bad. She attended school, where she excelled despite her shy demeanor. At home, Clara loved to hear her father’s war stories. When she was eleven, Clara’s older brother David fell off a barn roof and was bedridden for the following two years. Young Clara helped nurse him back to health. These experiences would prove beneficial, and at times crucial, to her humanitarian work later in life.

Clarissa Harlowe Barton was born on Christmas Day (December 25th) 1821 in Massachusetts. The youngest child, with four much older siblings, Clara did not have an easy childhood. Her mother was not kind to her. Her siblings were more parents than playmates. However, Clara’s childhood wasn’t all bad. She attended school, where she excelled despite her shy demeanor. At home, Clara loved to hear her father’s war stories. When she was eleven, Clara’s older brother David fell off a barn roof and was bedridden for the following two years. Young Clara helped nurse him back to health. These experiences would prove beneficial, and at times crucial, to her humanitarian work later in life.

Clara Goes to Work

At the age of eighteen, Clara Barton went to work: not as a nurse, but as a teacher. In the 1800s in the United States, nursing was a predominately male profession. Teaching was one of the few careers available to women. But that wasn’t the only reason Clara taught; she both excelled at teaching and enjoyed it. She began teaching near her home in Oxford, Massachusetts, then went on to start a school from the children of her brother’s mill workers, and finally established the first free public school in the town of Bordentown, New Jersey. Barton’s Bordentown school was a huge success, so successful that the powers-that-be in the town felt it was necessary to hire a male principal to run the school. Clara, who had established the school and built it up, was outraged.

“I may sometimes be willing to teach for nothing, but if paid at all, I shall never do a man’s work for less than a man’s pay.”

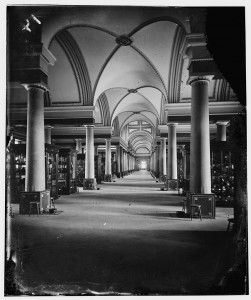

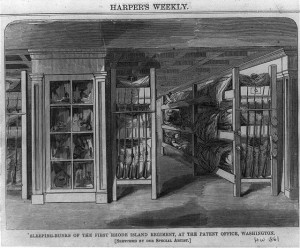

US Patent Office, Courtesy of the Library of Congress

Indignant, Clara left Bordentown and stopped teaching. She moved to Washington, DC and began her second career: working for the U.S. Patent Office. Clara was one of the earliest women to work for the federal government … and it was not easy. Many of Barton’s male coworkers harassed Clara and tried to besmirch her good name and get her fired. Lucky for Clara, she had a great boss who defended her and refused to dismiss her due to hearsay. Instead, he saw her talents and drive, and is believed to pay Clara Barton the same wage as a man. However, when her boss changes, she is demoted to a copyist.

This didn’t last forever. Although Clara had a supportive boss, there were many men in the government who were opposed to women working in their midst. Secretary of the Interior Robert McClelland demoted Clara to a copyist who only earned 10 cents per every 100 words copied.

In 1857, James Buchanan won the presidential election and fired his opponent’s outspoken supporters, including Clara. She returned home to Massachusetts to wait out Buchanan’s term. In the interim, she helped out in the homes of her friends and family members. Clara was never meant to be a homebody. She was miserable.

In 1861, Abraham Lincoln took office and Clara returned to Washington, DC and to the Patent Office. She, however, would never return to the position of clerk and the equal salary she enjoyed. She moved into a boarding house on 7th Street, two blocks from the Patent Office. Today, that boarding house is our museum.

The Country Goes to War

No one ever said 1861 was an uneventful year in the United States. In April of 1861, the Battle of Fort Sumter marked the beginning of the American Civil War. Union troops flooded into Washington, DC.

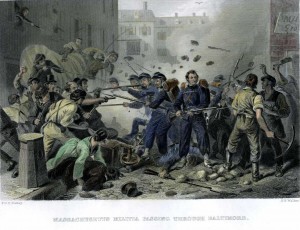

The 6th Massachusetts Infantry was among these troops. While switching trains (and train stations) in Baltimore, the regiment was attacked by a mob of Confederate sympathizers. Members of the mob tore up the street’s paving stones, and threw them at the soldiers. Others jeered at the soldiers, with pistols and muskets in their hand. Then someone fired a shot, which led to more shots and more stone throwing from both sides. Finally the police arrived and put an end to the violence. The police escorted the soldiers to Camden Street station and their train to Washington.

The 6th Massachusetts Infantry was among these troops. While switching trains (and train stations) in Baltimore, the regiment was attacked by a mob of Confederate sympathizers. Members of the mob tore up the street’s paving stones, and threw them at the soldiers. Others jeered at the soldiers, with pistols and muskets in their hand. Then someone fired a shot, which led to more shots and more stone throwing from both sides. Finally the police arrived and put an end to the violence. The police escorted the soldiers to Camden Street station and their train to Washington.

The Baltimore Riot resulted in the first casualties of the Civil War. Eight of the Confederate sympathizers were killed, along with three soldiers, and one innocent bystander. Twenty-four soldiers were wounded.

The news of the riot arrived in Washington before the train did. Clara, along with many other women, were at the station to meet the train. When the soldiers emerged, Clara discovered they were her old friends, school mates, and students from Massachusetts. She sprung into action, organizing who should go where for treatment and rest.

In the following days, more and more soldiers arrived in Washington. They were everywhere. Without suitable barracks, soldiers set up camp in government buildings. The Sixth Massachusetts camped on the floor of the Senate. The First Rhode Island regiment slept on the shelves of the Patent Office. Clara visited old friends and made new acquaintances. She also noticed that not only did the troops have nowhere to camp, they were sorely without supplies.

In the following days, more and more soldiers arrived in Washington. They were everywhere. Without suitable barracks, soldiers set up camp in government buildings. The Sixth Massachusetts camped on the floor of the Senate. The First Rhode Island regiment slept on the shelves of the Patent Office. Clara visited old friends and made new acquaintances. She also noticed that not only did the troops have nowhere to camp, they were sorely without supplies.

Clara was determined to fix this. She began collecting supplies, first in her neighborhood, then from her friends in Massachusetts and New Jersey. Soon, Barton had acquired three warehouses full of supplies, and had to figure out how to get them to the soldiers.

Clara Goes to War

Getting the supplies to the soldiers was easier said than done. Clara wanted to deliver the supplies herself, but was apprehensive how the soldiers would treat her. After all, there were names for the women that hung around camp … and not nice names. After much soul searching, and even more permission searching, Clara had gathered both the permission and resolve to deliver supplies to the troops at the field hospitals set up outside the Battle of Cedar Mountain. She arrived at the camp and immediately got to work. She worked for days on end, without rest, then collapsed with exhaustion when she returned home. Throughout the war, Clara continued this pattern: collect supplies, visit field hospitals (and later on the battlefields themselves) and work fervently, then collapse, exhausted, ill, and at times depressed. Repeat.

When Johnny Doesn’t Come Marching Home

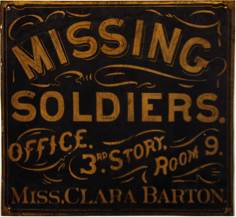

Courtesy of the U.S. General Services Administration

As the Civil War drew to a close, Clara Barton was not ready to end her war work. She loved being useful and serving those in need. She had to find a new way to help. Her solution was the Missing Soldiers Office. Tens of thousands of men were missing. Their friends and families wrote to Clara, asking, have you seen Wilber? Joseph? Thomas? Clara Barton and her small staff received over 63,000 requests for help. They were able to locate over 22,000 men, some of whom were still alive.

Of the 22,000 men located by the Missing Soldiers Office, 13,000 were in one place: Andersonville Prison. These men were located due to the cunning and courage of another soldier: Dorence Atwater. Atwater had been imprisoned in Andersonville. As a prisoner, he was responsible for burying the men who passed away, and keeping a list of their names and the locations of their graves for the Confederate government. Atwater secretly kept a duplicate list for himself. When the war ended, he wanted to publish the list. He ultimately turned to Barton to do so. Together they not only published the list naming 13,000 men who died in Andersonville, they ensure each of the 13,000 men’s graves were marked.

What Comes Next?

In 1868, Clara was exhausted from years of working for soldiers. Her doctors recommended she go to Europe to rest, so Clara packed up her things—leaving many of them in the attic of her boarding house rooms—and headed off for Europe and a break.

When Clara got to Europe, she didn’t relax. Instead, she met representatives from the International Red Cross who inspired her to found the American Red Cross. However, before returning to the states, Clara provided nursing and humanitarian assistance during the Franco-Prussian War.

Damage caused by the Johnstown Flood of 1889, Courtesy of the Library of Congress

Once back in America, Clara did found the American Red Cross, and set the precedent that the Red Cross will respond to natural disasters, in addition to war. Clara also advocated for America to ratify the Geneva Convention. Clara worked tirelessly to serve others for the rest of her life. She responded to the Johnstown Flood and the Galveston Hurricane, she even helped out in Armenia and Cuba. She served as president of the American Red Cross until 1904, when at the age of 82 she resigned, then started the National First Aid Association of America. At the age of ninety, Clara Barton died in her home in Glen Echo, Maryland in 1912. Today, we celebrate her legacy and tell her story.