Clara Barton’s Missing Soldiers Office: 1865-1868

“The prospects of a speedy peace either in the conquest or the submission of the South has never been so cheering,” the New York Herald triumphantly declared on January 1, 1865. To delay its imminent defeat, the Confederacy reestablished the practice of prisoner exchange in early 1865.[1] A result of the resumed exchanges was thousands of emaciated and desperately ill former Union prisoners from infamous camps like Andersonville and Belle Isle began arriving at a designated drop-off point known as Camp Parole, near Annapolis, Maryland.

At the beginning of 1865, Clara Barton had returned to Washington to nurse her brother Stephen and nephew Irving Vassall who had both fallen ill. While Barton was in Washington, Vassall, a government employee, had heard news that exchanged Union prisoners were returning in poor condition and that the government needed help notifying the relatives of those who were missing or had died in captivity. Vassall relayed the information to Barton in the hope that she might be able to offer assistance. Barton empathized deeply with families suffering loss, because she would eventually lose both Stephen and Irving that same spring.

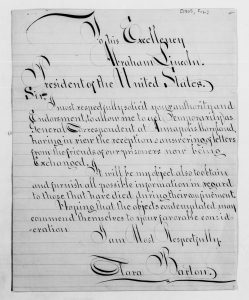

In February 1865, Barton wrote to President Abraham Lincoln in pursuit of permission to become an official government correspondent seeking those who had vanished during the conflict. In an effort to capture the attention of a man besieged by correspondence, she wrote her letter in exceedingly grandiose script.

Barton’s letter to Lincoln, February 1865. Courtesy of the Library of Congress

To his Excellency Abraham Lincoln President of the United States

Sir, I most respectfully solicit your authority and endorsement to allow me to act temporarily as general correspondent at Annapolis Maryland, having in view the reception and answering of letters from the friends of our prisoners now being exchanged.

It will be my object also to obtain and furnish all possible information in regard to those that have died during their confinement.

On March 24, 1865, Barton received the sanction of the president to go to Annapolis in an official capacity. Her job would be to list the names of those who died in captivity and notify their families.

Word quickly spread around the nation about Barton’s appointment to look for missing soldiers through the newspapers. Even by 1865, Barton had developed a reputation as a friend of the soldier. She often traveled to battlefields to help the sick and wounded, so loved ones occasionally sent her letters inquiring if she had seen their relatives. Barton’s official appointment meant she received thousands of letters (sometimes as many as 150 a day) from concerned relatives, primarily women, looking for loved ones.

At Annapolis, Barton witnessed chaos as thousands of emaciated former prisoners disembarked from the vessels that carried them to freedom from Confederate prisons. As the weakened men struggled from the ships, Barton noted that inconsistent record-keeping made it almost impossible to know who had been left behind in the graveyards at the prisons. In lieu of official reports, Barton turned to the best source of information she had on-hand: the soldiers themselves. She implored the returning soldiers to tell her about their comrades who did not make the return journey.

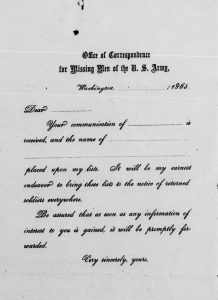

To meet the astonishing demand of letters, Barton hired a few assistants with her own money, expecting the government would eventually reimburse her. Barton and her small team were able to keep up with the overwhelming rate of incoming inquiries with form letters. A few well-placed blank lines allowed Barton to respond more efficiently to the many concerned writers. “Your communication of ______ is received, and the name of _______ placed upon my lists. It will be my earnest endeavor to bring these lists to the notice of returned soldiers everywhere. Be assured that as soon as any information of interest to you is gained, it will be promptly forwarded.”

An example of the form letters Barton and her team sent out to keep up with the massive demand.

Barton refused to take money from those desperately searching for lost relatives. She even refused donations as little as one dollar on a matter of principle.

Gradually she compiled a master list of soldiers who had disappeared during the Civil War. In June 1865, she published the first “Roll of Missing Men” which listed 1,533 names. By the conclusion of her work in 1868, five separate rolls were published containing 6,650 names. These lists organized the names by state, and contained instructions for anyone, with knowledge of these men’s whereabouts to write to her. President Andrew Johnson allowed Barton to use the larger government printing press to publish the Rolls of Missing Men, a task that would have been prohibitively expensive otherwise.

Barton explained to one concerned writer how she curated the names on her Rolls of Missing Men: “The appearance of a man’s name upon my roll is simply evidence that some friend is asking for him…and the non-appearance signifies that he has not been inquired for or there has not been time to get his name upon a roll.”

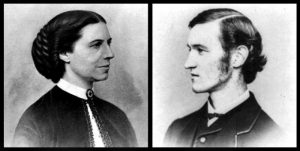

Clara Barton and Dorance Atwater

After Camp Parole closed, Barton decided to continue searching for missing soldiers. A meeting with Dorence Atwater in June 1865 propelled her mission to new heights. Atwater kept a hidden and detailed list of those who died at the notorious Andersonville Prison during his time in captivity there. After seeing the first Roll of Missing Men, he decided to contact Barton to offer his help. Atwater’s information enabled an expedition, which included Barton, to go to Andersonville, identify the graves of 13,000 missing soldiers, and notify the families. The team eventually established a national cemetery at the location of the prison. The whole process lasted through the middle of August.

Francis Dana Barker Gage

As a part of the Andersonville team, Barton played a significant role in bringing closure to thousands of families, but she was unsure how much longer she could continue to search for missing men without extra money as her personal funds were beginning to run dry. It was not until early 1866 with the assistance of her friend Francis Dana Barker Gage that Barton was able to raise money to continue her work. Gage wrote several pleas for Barton in the New York Independent soliciting money for her noble cause. Gage also helped Barton draft a petition to send to Congress. After much deliberation, Congress elected to grant her $15,000 as a reimbursement for her previous efforts and to keep the mission going. With that boost, Barton was able to continue the work of the Missing Soldiers Office through the end of 1868.

In her final report to Congress, Barton presented some amazing numbers. In four years the Missing Soldiers Office “had received 63,182 inquiries, written 41,855 letters, mailed 58,693 printed circulars, distributed 99,057 copies of her printed rolls, and identified 22,000 men.”[2]

As someone who had seen and helped to ease so much physical trauma on Civil War battlefields, Barton recognized how important the work of finding missing men was to sooth the minds of loved ones at home. Barton herself tried to describe the inspiration that kept her moving in spite of challenging circumstances in a letter to a benefactor:

If it has been my privilege to lighten ever so little the heavy burden of grief which has been laid upon the hearts of our suffering people, or throw the feeble weight of my arm on the side of my country in her hour of trail, if I have made one heart stronger, or one war less bitter, I regard it as a blessing forever beyond my power to express. And whatever yet remains to be done, or however weary I may become even in well doing, my soul will always be lifted up, my hands strengthened, my step quickened, and the miles shortened by the reflection that the hearts of good men and women are with me in my work; that I carry their respect and approval, and that their generous consideration is helping me on to its accomplishment.

[1] The Confederacy had stopped exchanging prisoners in 1863 when the Union allowed units of African-American troops to serve. As time went by the excess of Union prisoners became a drain on Southern resources, and the Confederacy needed more men to fill its thinning ranks. They therefore resumed the practice of prisoner exchange in early 1865. Read more about it here.

[2] Stephen B. Oates Woman of Valor: Clara Barton and the Civil War (New York: The Free Press, 1994), 368.