“May this Quilt Comfort Your Body and Spirit:” Album Quilts for Soldiers

During the early winter months of 1863, Rebecca Pomroy, a nurse at the Columbian College hospital in Washington, DC, received a quilt from a group of ladies in the Northeast. It was constructed of blocks of small, multi-colored squares around a center white square that bore handwritten inscriptions in ink—features that defined it as an album quilt. The messages on the white squares contained a variety of sentiments, from Bible passages and patriotic slogans, to inspiring phrases and riddles such as, “Why are soldiers like tea? Because, when in fire, they are well drawn out.” Rebecca remembered in her post-war memoir that “a vast store of amusement was stitched into this beautiful piece of work for the lonely patients.”

The brightly colored-album quilt, with its entertaining inscriptions, proved to be a valuable addition to the hospital that winter. After it was sent through the wards for all to see, Rebecca, recognizing the great joy it brought soldiers, reserved it for only the sickest and those near death. She would bring it around and let each man spend an hour with it, gazing upon the beautiful colors and rereading the comforting messages. For one terminal soldier the quilt was the only thing that could calm him during his final hours. This simple album quilt with its patchwork squares and notes exceeded its purpose as bedding and provided needed emotional support and entertainment to soldiers.[i]

Album quilts were one of the most popular items made by women for soldiers during the Civil War in both the North and South. Their patchwork squares made them well-suited for communal construction and required each maker to contribute only small amounts of fabric—that could range in color and material—for their individual section. As fabric was scarce during the war, groups frequently opted to make album quilts rather than blankets that required yards of the same cloth. Oftentimes, women would even cut their squares from their clothing to give their sections an added personal touch.[ii]

Perhaps the most defining—and arguably most important—characteristic of album quilts were the handwritten messages inscribed on the squares. These notes often included names, hometowns, the year, and inspiring patriotic or religious phrases. While the intended primary use of these quilts may have been as bedding, they were valued more as entertainment. Additionally, beyond this use as recreation, these heartfelt messages also indicated to soldiers that even strangers, many miles away, were thinking of them and grateful for their service. Though the understanding of mental health at the time was very simple, these inscriptions became a form of emotional support for soldiers feeling low from wounds or illness, or from the isolation of military life. The importance of this support, although simple, cannot be overlooked; these men, taken out of the nurturing environment of antebellum home life, needed this type of familial comfort to boost their spirits.

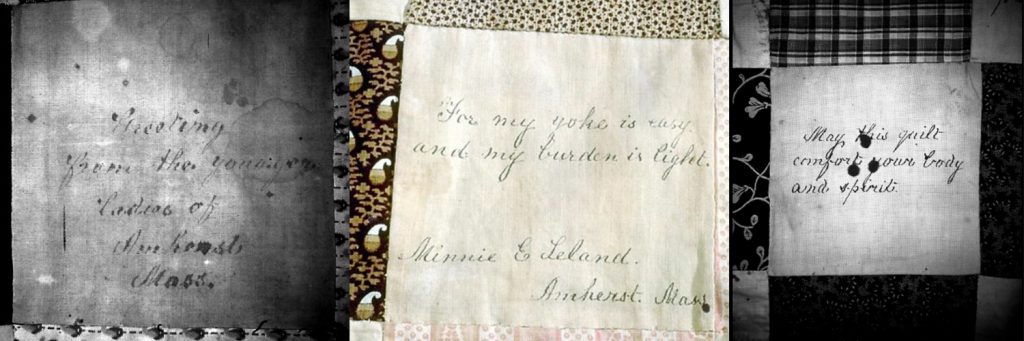

Details of inscriptions on an 1864 quilt from Amherst, Massachusetts.

Once finished, completed quilts would either be sent to a soldier’s aid society, such as the United States Sanitary Commission in the North, for distribution, or given directly to a hospital. Some groups attached notes to their quilts asking the recipients for correspondence. Many soldiers responded with letters, and some were even printed in local newspapers. These letters, filled with appreciation and praise from soldiers, provided crucial encouragement and assurance to women engaged in quilt-making projects. In one such published letter, R. Fuller, a hospitalized soldier in Kansas City, Missouri, graciously thanked one of the ladies that contributed to the quilt he was using. He wrote,

I am a sick soldier in hospital at this place, and one day while reading the names of the ladies, written on a quilt, I saw your name subscribed Fidelia Nash…Having received the benefit of a quilt made by your society, you will permit me to thank you, and through you the kind and benevolent ladies of your Aid Society. May God bless you all is the sincere wish of a sick soldier.[iii]

In addition to penning these encouraging letters, some soldiers even placed ads in newspapers for these quilts. In early 1864, soldiers at the Armory Square Hospital in Washington, D.C. were so grateful for an album quilt they received, that they placed an advertisement in their hospital gazette asking more women to send similar quilts to soldiers in hospitals.[iv]

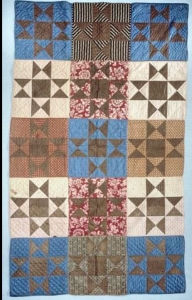

Two quilts made in New England during the war perfectly illustrate the value of album quilts. In Augusta, Maine during the late summer of 1863, Susannah Pullen and the fourteen young ladies of her Sunday school class designed a star-patterned album quilt to send to hospitalized Maine soldiers. Each girl worked on her own block and filled the pieces of the stars with inscriptions. While most of the 150 messages on the quilt are religious or patriotic, there are a few light-hearted notes, such as, “if you are good looking send me your photograph.” One girl even included some helpful health advice on her section, writing, “wash the feet well every night, it aids to keep the skin and nails soft and to prevent chafing, blisters, and corns, all of which greatly interfere with a soldier’s duty. This is more important than to wash the face and hands in the morning.”

Susannah Pullen’s Sunday School Quilt 1863. National Museum of American History

On the back of the quilt Susannah penned a note expressing her desire for correspondence from the quilt’s recipients. She wrote, “any proper letters from any persons embraced in the defense of our country, received by any whose names are on this quilt shall have a reply…your letters would prompt us to more exertions for our patriots.” Later that November, Pullen and her pupils received a letter from Sergeant Nelson S. Fales at the Armory Square Hospital praising them for their work. He wrote, “Dear Madam I have had the pleasure of seeing the beautiful ‘Quilt’ sent by you to cheer and comfort the Maine Soldiers. I have read the mottoes, sentiments, etc., inscribed thereon with much pleasure and profit.” This response from Sergeant Fales confirmed that they succeeded in achieving their goal of providing aid to soldiers.[v]

A year later in Amherst, Massachusetts, a large group of women and children constructed a sizable album quilt with 384 squares of alternating printed and white cottons. The makers inscribed each white square with their names, religious and secular messages, as well as the date and their location in Amherst. Among the numerous inscriptions were, “three cheers for the Red, White & Blue 1864,” “God save Gen. Grant and his brave men,” and “may this quilt comfort your body and spirit.” On several squares, underneath the note, is the signature “the children of Amherst”—the ladies directing the project clearly wanted the recipients to know that even children cared for the soldiers. This album quilt, the product of a large community effort, was later used in a Union hospital.[vi]

Album quilts were not only articles of bedding, but objects that provided emotional comfort. For men with hours of inactivity ahead of them, having something to look at and pass the time was invaluable. Album quilts also gave women the opportunity to actively contribute to the war effort. Their sewing skills took on new value – providing a significant morale boost to soldiers. In short, album quilts had an importance that went well beyond mere creature comfort.

End Notes

[i] Anna L. Boyden, War Reminiscences: A Record of Mrs. Rebecca R. Pomroy’s Experience in Wartimes (Boston: D. Lothrop Company, 1884), 124-125

[ii] Madelyn Shaw and Lynne Zacek Bassett, Homefront and Battlefield: Quilts and Context in the Civil War (Lowell, MA: American Textile History Museum, 2012), 94-95; Virginia Gunn, “Quilts for Union Soldiers in the Civil War,” in Quiltmaking in American: Beyond the Myths, ed. Laurel Horton (Nashville, TN: Rutledge Hill Press, 1994), 90-91.

[iii] Gunn, “Quilts for Union Soldiers,” 87.

[iv] Armory Square Hospital Gazette, February 2, 1864

[v] Susannah Pullen’s Civil War Quilt. Accession number 138338. Online object record. National Museum of American History.

[vi] “1864 Album Quilt Top.” Accession number 272176. Online object record. National Museum of American History.

About the Author

Kristen Hunter is a graduate student at George Mason University studying the History of Decorative Arts. She is currently completing her Master’s thesis, “By Her Needle and Thread,” which looks at how women used material objects of their production to shape their families’ experiences of the Civil War. She also holds a BA in History from Villanova University.

Tags: Album Quilts, Armory Square Hospital, Civil War hospitals, civil war medicine, Quilts, United States Sanitary Commission Posted in: Uncategorized