Thanksgiving & the Civil War

The celebration of Thanksgiving is an integral and unifying component of American culture. Thanksgiving Day, as we know it in 2014, did not become a national holiday until the Civil War.

|

| President Lincoln & Sarah J. Hale |

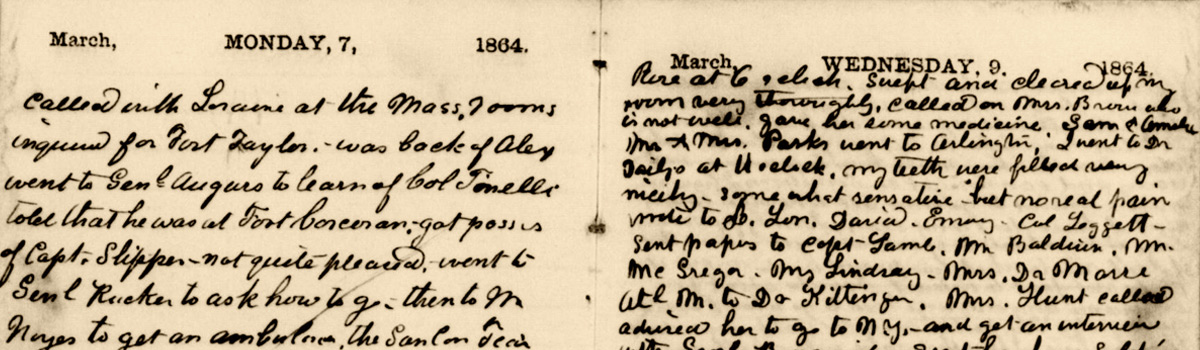

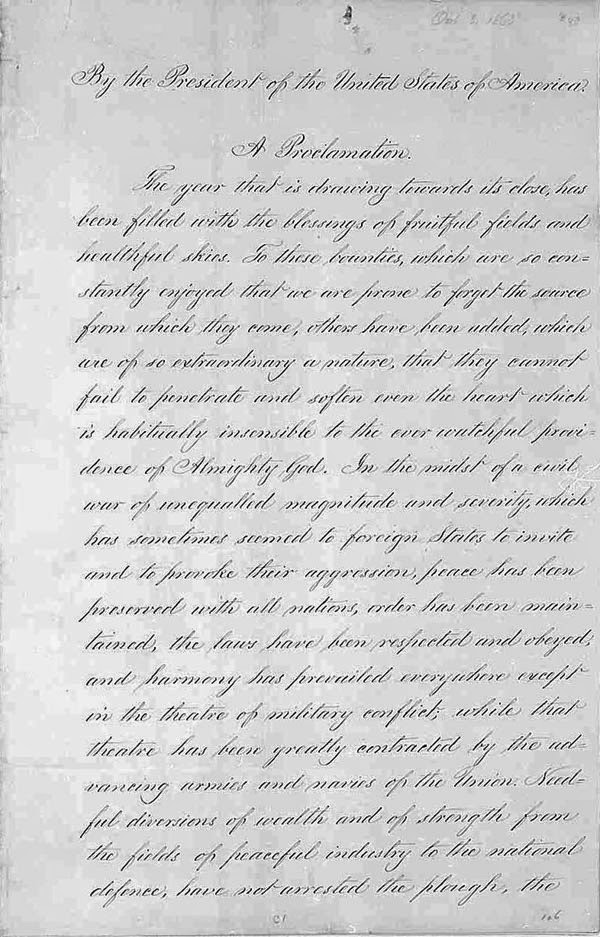

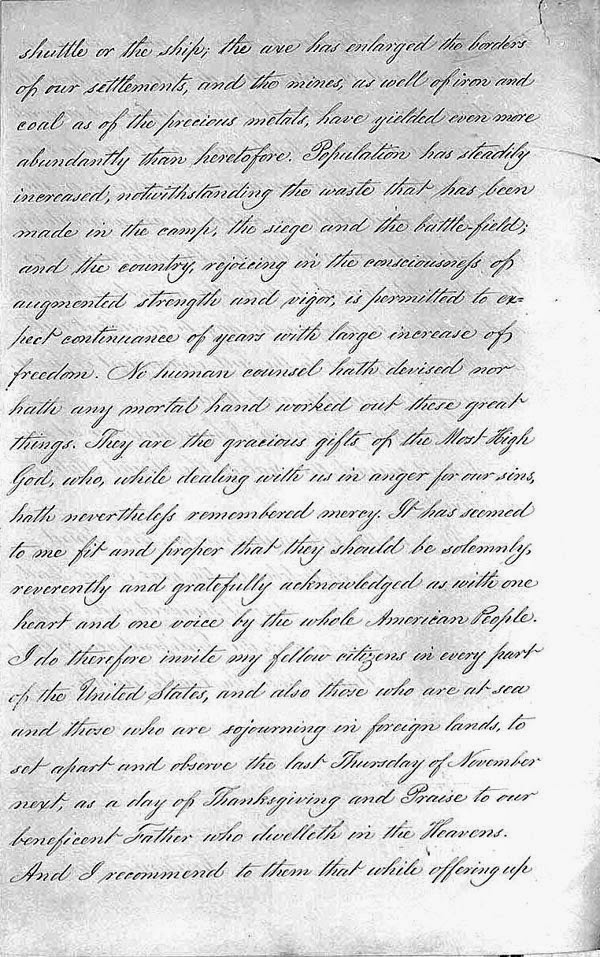

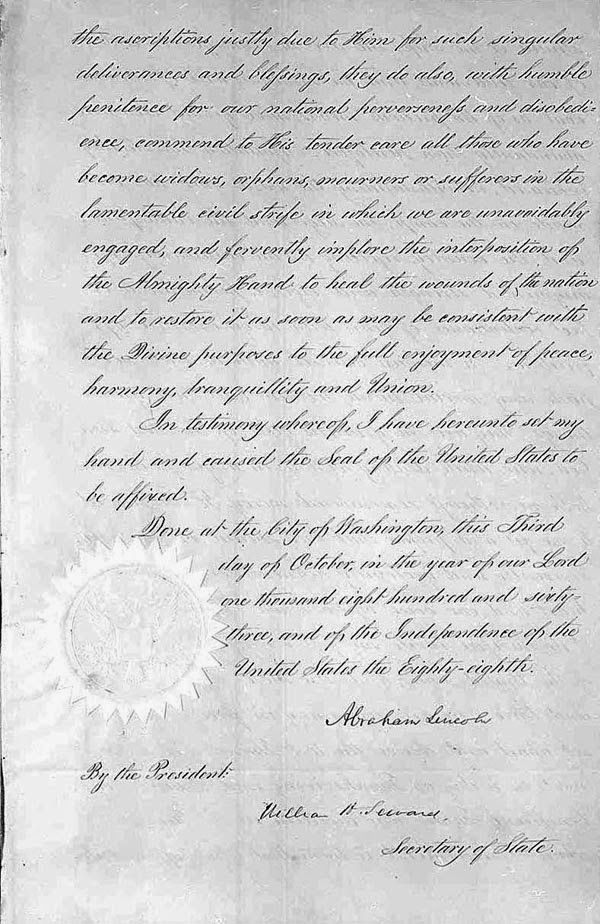

On November 29, 1860, the newly-elected Abraham Lincoln shared an unofficial Thanksgiving celebration with his family, which included a meal of roast turkey. This was three years before he received a letter from Sarah Josepha Hale, an editor of a popular women’s magazine. Hale lobbied President Lincoln to encourage him to establish a national day of Thanksgiving. Known as the “Mother of Thanksgiving,” she understood the holiday’s potential as a means of unification for a nation strongly divided along social, economic, and ideological lines. Her letter to Lincoln brought about the results she desired: on October 3, 1863, Lincoln issued a Thanksgiving Day Proclamation that officially established the custom as a national holiday. This Proclamation, written by Secretary of State William Seward, offered a hopeful message:

In the midst of a civil war of unequaled magnitude and severity, which has sometimes seemed to foreign States to invite and to provoke their aggression, peace has been preserved with all nations, order has been maintained, the laws have been respected and obeyed, and harmony has prevailed everywhere except in the theatre of military conflict.

President Lincoln’s Thanksgiving Day Proclamation

During the Civil War, the holiday remained a cultural tradition celebrated locally by communities in different regions of the United States. Similarly, both the Union and the Confederate Armies held periodic and separate days of thanksgiving in response to military victories. On August 6, 1863, for example, the Union held a day of thanksgiving in honor of its success at the Battle of Gettysburg (July 1-3). On November 26, 1863, President Lincoln held the first official Thanksgiving Day celebration.

Where was Clara Barton in 1863 and how did she observe the newly established holiday?

HILTON HEAD & MORRIS ISLAND, SOUTH CAROLINA

|

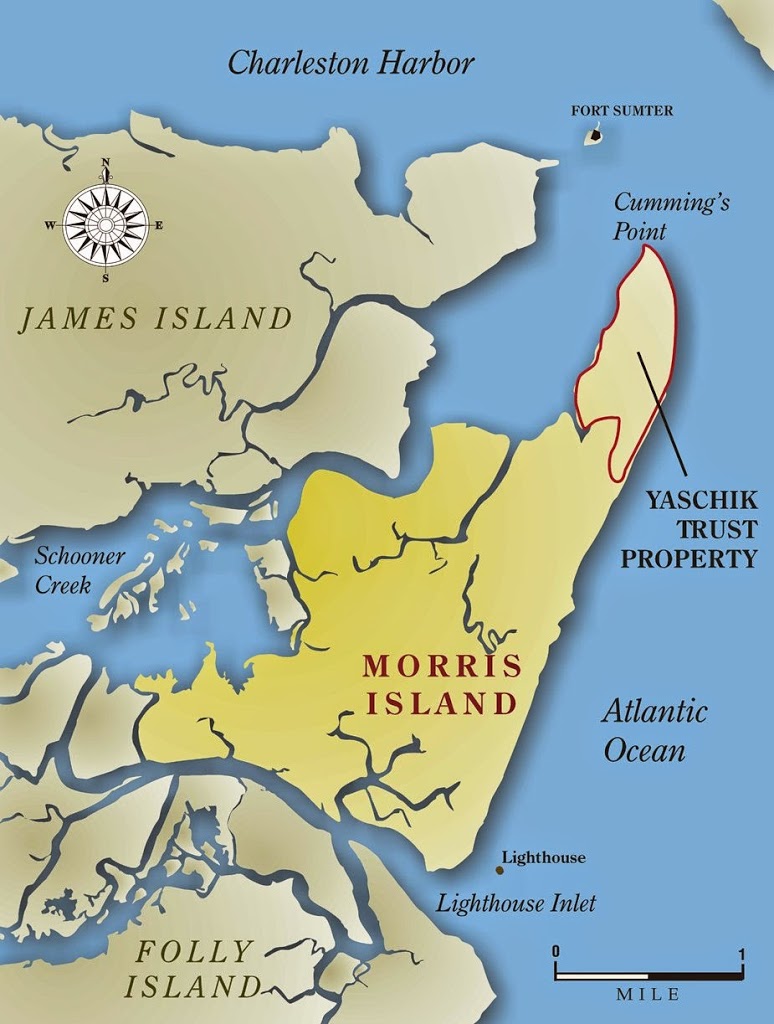

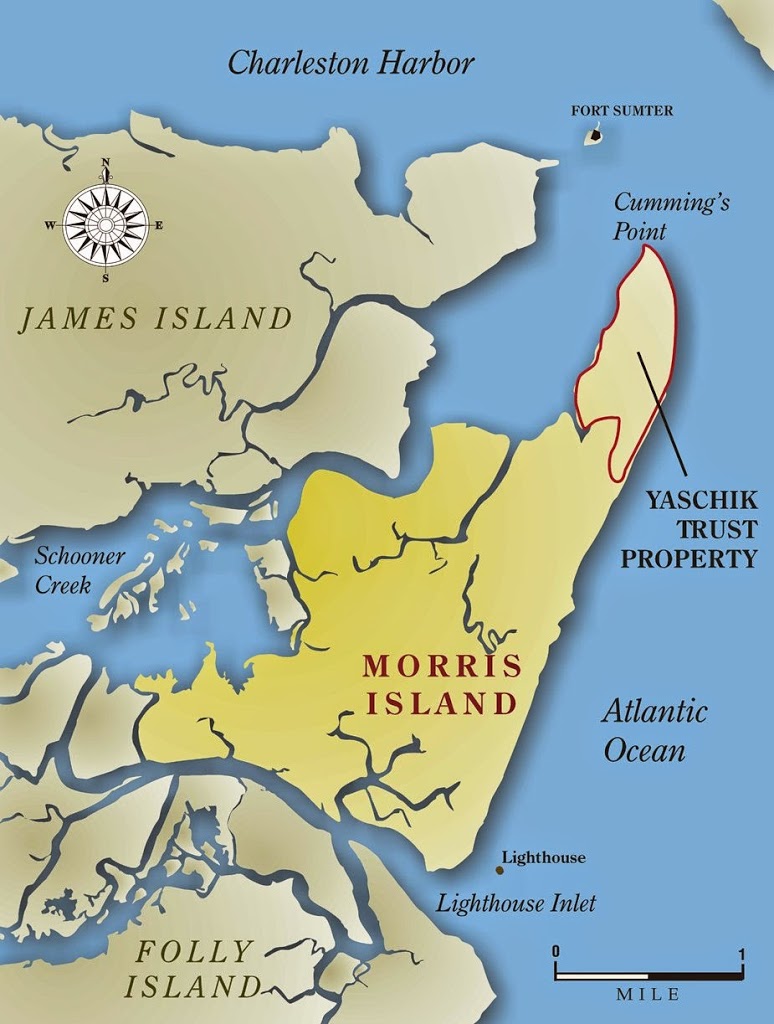

| Map of Morris Island, SC |

Throughout 1863, Clara Barton traveled between Hilton Head and Morris Island, South Carolina. When the battle of Battery Wagner broke out on July 18, Miss Barton sprang into action to help wounded soldiers.

|

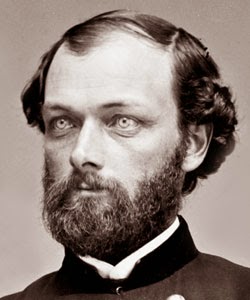

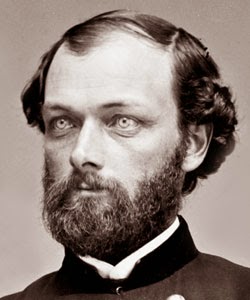

| Col. Robert Gould Shaw |

|

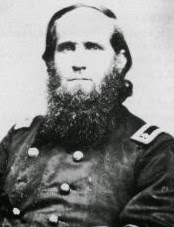

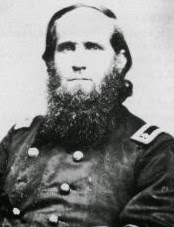

| Brig. Gen. Quincy Gillmore |

Union Brigadier General Quincy Gillmore initiated the battle of Battery Wagner. Gillmore planned to seize the Confederate fort on Morris Island in an effort to use Cummings Point as a strategic location to attack the Confederate Army at nearby Fort Sumter. On July 18, Gillmore sent the 54th Massachusetts regiment, led by Colonel Robert Gould Shaw, to attack the narrow beach at Battery Wagner. As the 54th Mass. neared the fort, they were subjected to artillery and musket fire that pinned down their exposed ranks. Despite the loss of 1,515 soldiers, the 54th Mass. bravely descended into the fort by engaging in bloody hand-to-hand combat with Confederate soldiers. The battle of Battery Wagner and the 54th Mass. were immortalized in the movie Glory (1989).

In her diary, Clara Barton recalls:

Weeks of weary siege scorched by the sun—chilled by the wave, rocked by the tempest. Buried in the shifting sands—toiling day after day in the trenches, with the angry fire of forts hissing during the day.

During one artillery assault, Miss Barton braved exploding shells and debris to rescue Colonel Robert Leggett, whom she found lying on the sand with his leg blown off at the knee. Clara Barton tore off some of her dress, tied the cloth into a tourniquet, and used it to stem the bleeding. Throughout the remainder of the battle, Miss Barton and her assistant Mary Gage walked the beach looking for survivors. If they found a living soldier, the women would call out to Union stretcher-bearers to bring him back to the beach hospital. In addition, Miss Barton and Miss Gage nursed wounded soldiers by feeding them and offering emotional support. Clara Barton rarely left the bedsides of wounded soldiers once they arrived at the beach hospital.

|

| Col. John Elwell |

In August 1863, Clara became exhausted and ill from lack of sleep, inadequate food rations, and the overall harsh conditions on Morris Island. Suffering from diarrhea and fever, her friend Colonel John Elwell instructed quartermasters to put her on a boat for Hilton Head where she could recover from her illness.

Miss Barton returned to Morris Island shortly before Brig. Gen. Gillmore succeeded in forcing the Confederate Army to abandon Battery Wagner on September 7, 1863. On September 15, Clara Barton received a letter from Gillmore’s office instructing her to leave Morris Island because her services were no longer needed. In her diary, she speculates that Gillmore believed she “was some frail creature who could not endure hardship.” He did not understand Clara at all, even after she rose from her illness and returned to her post. The sexual discrimination that Clara Barton faced on Morris Island caused her great humiliation and anguish. With a heavy heart, Miss Barton conceded to Gillmore’s instructions and left Morris Island for Hilton Head.

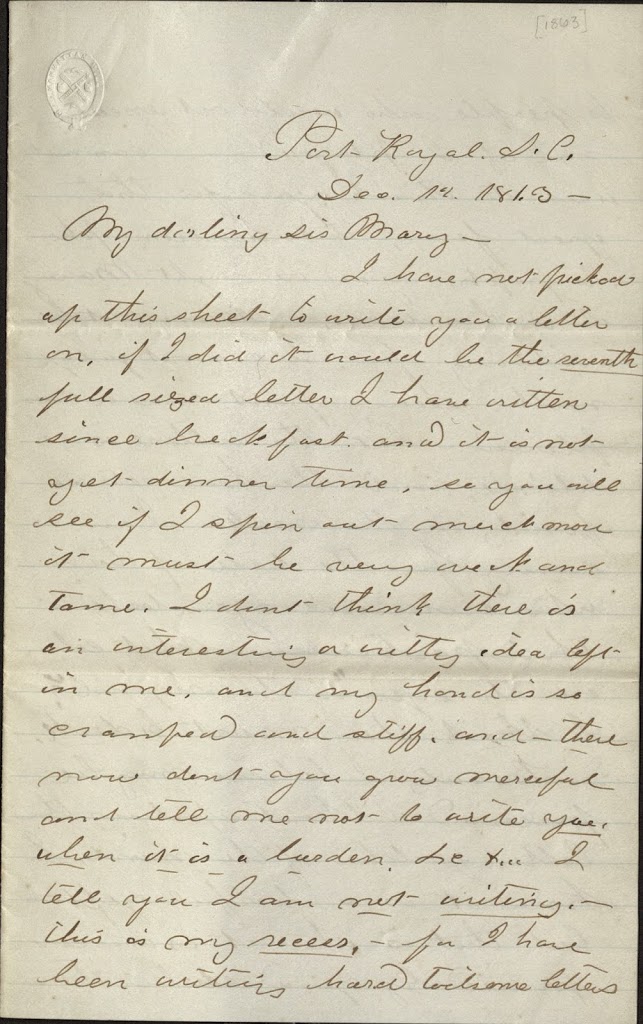

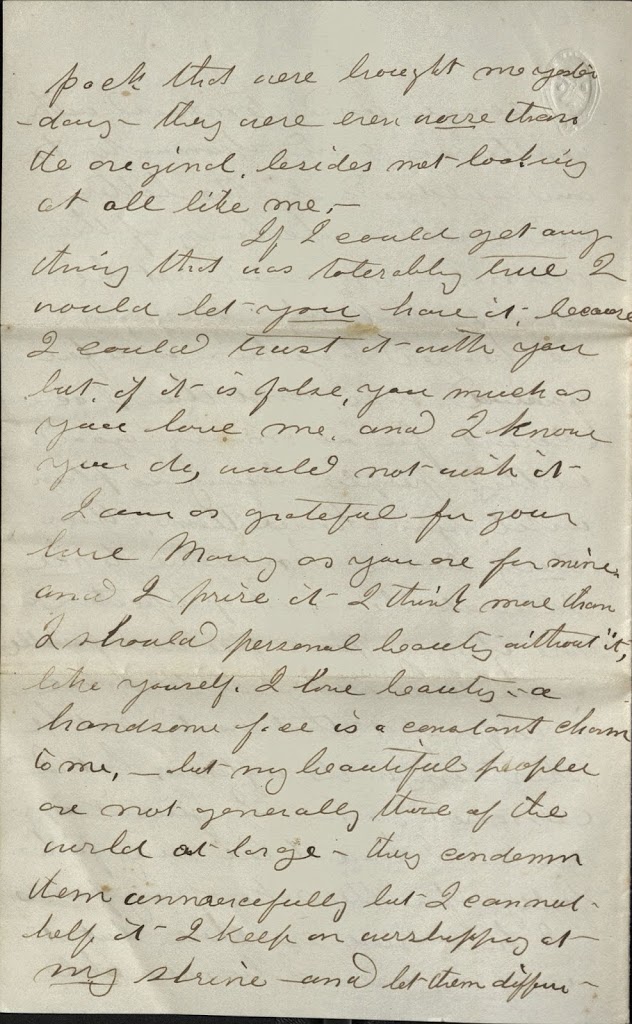

NOVEMBER 1863

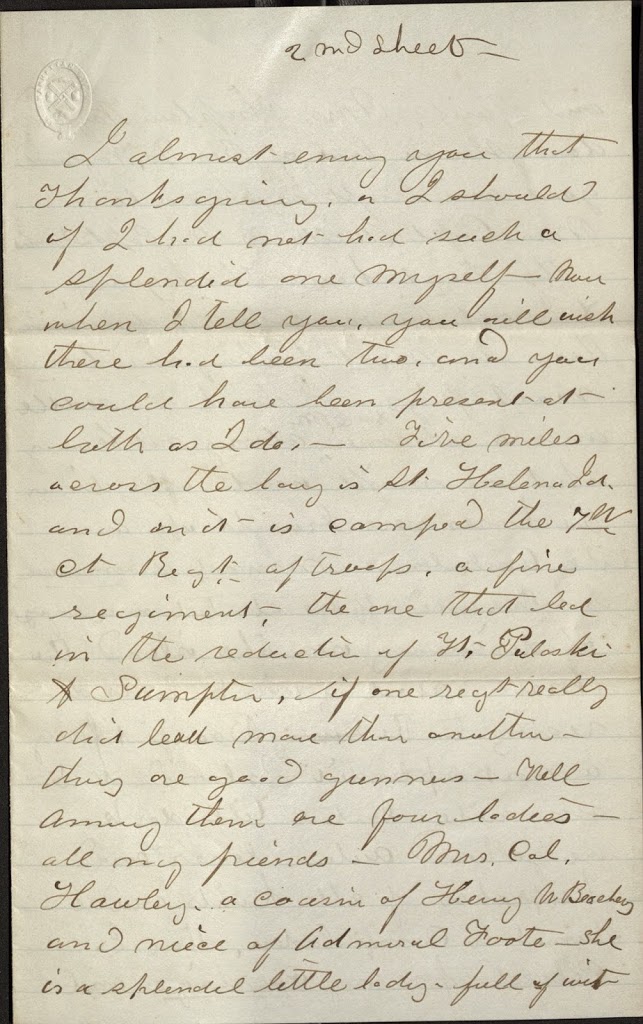

On November 11, 1863, Col. Elwell managed to secure a pass from Gillmore’s office for Clara Barton’s return to Morris Island. The U.S. Sanitary Commission invited Clara to care for each dying soldier on the Island “as if she were his mother or sister.” Now Miss Barton had a decision to make: should she return to Morris Island for the winter or move back to Washington, D.C.? On November 12, Miss Barton wrote a letter to her best friend Mary Norton asking what to do:

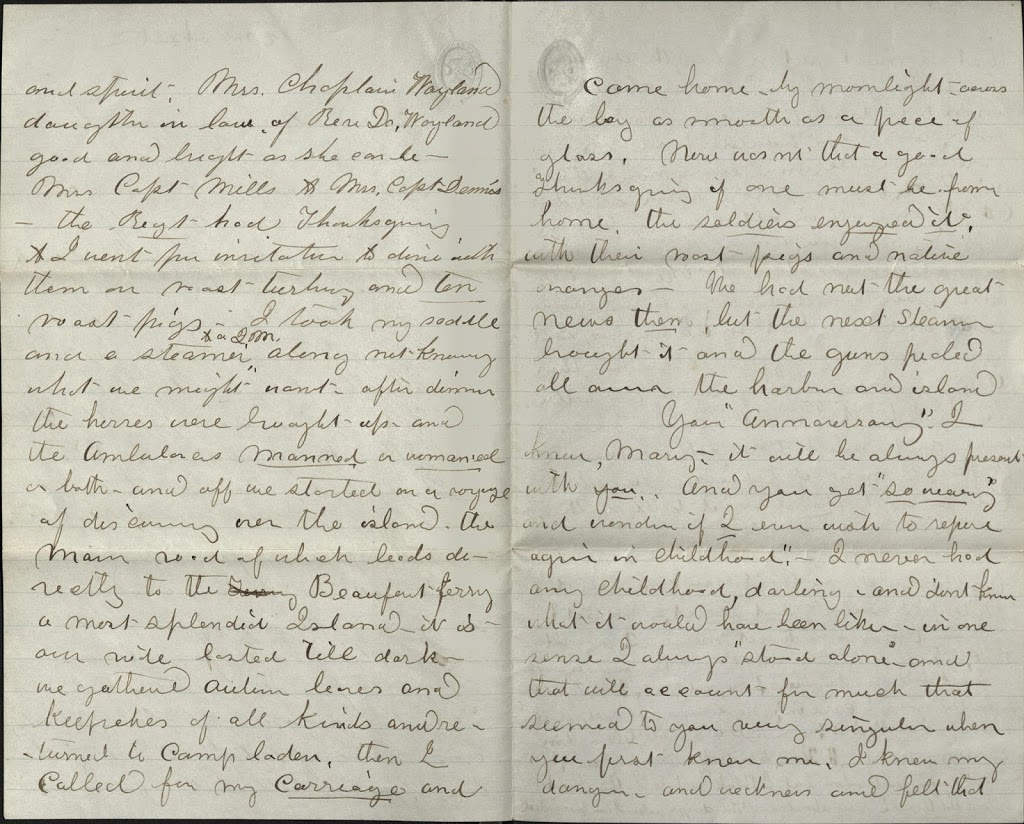

My friends here at the Head are trying to keep me from going to Morris Island this winter now that there is so little doing there, and to coax me off the notion, they have built me a most beautiful suite of rooms—and I think perhaps I ought to remain with them unless the troops move…So what shall I do?—and I know you will tell me to remain at Hilton Head and keep comfortable this winter. Well, I don’t know—perhaps I ought—but will watch and see and tell you.

Clara Barton, Letter to Mary Norton, November 12, 1863, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University, Durham, NC

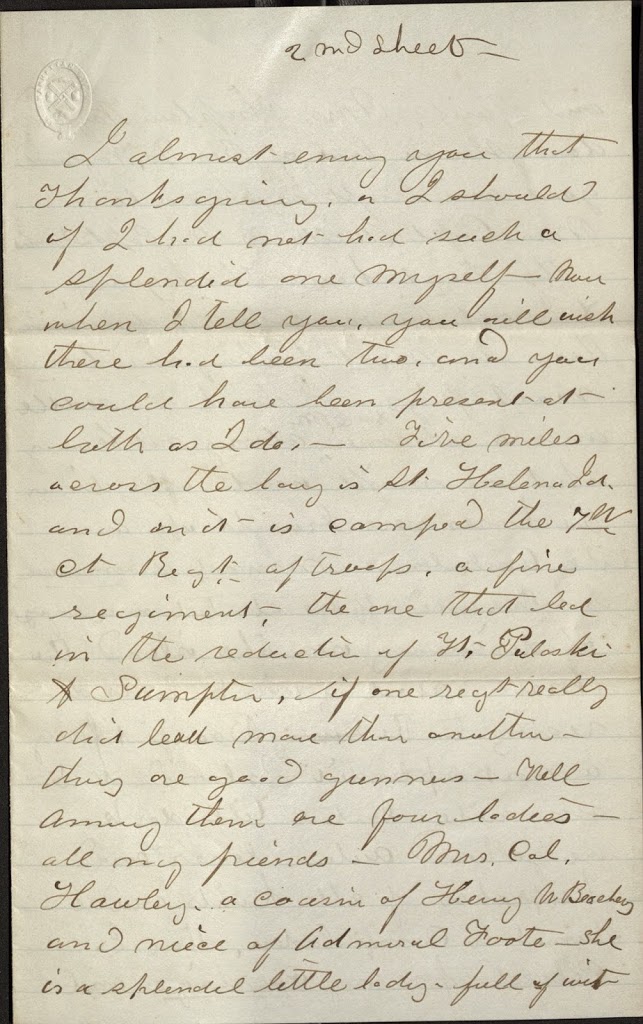

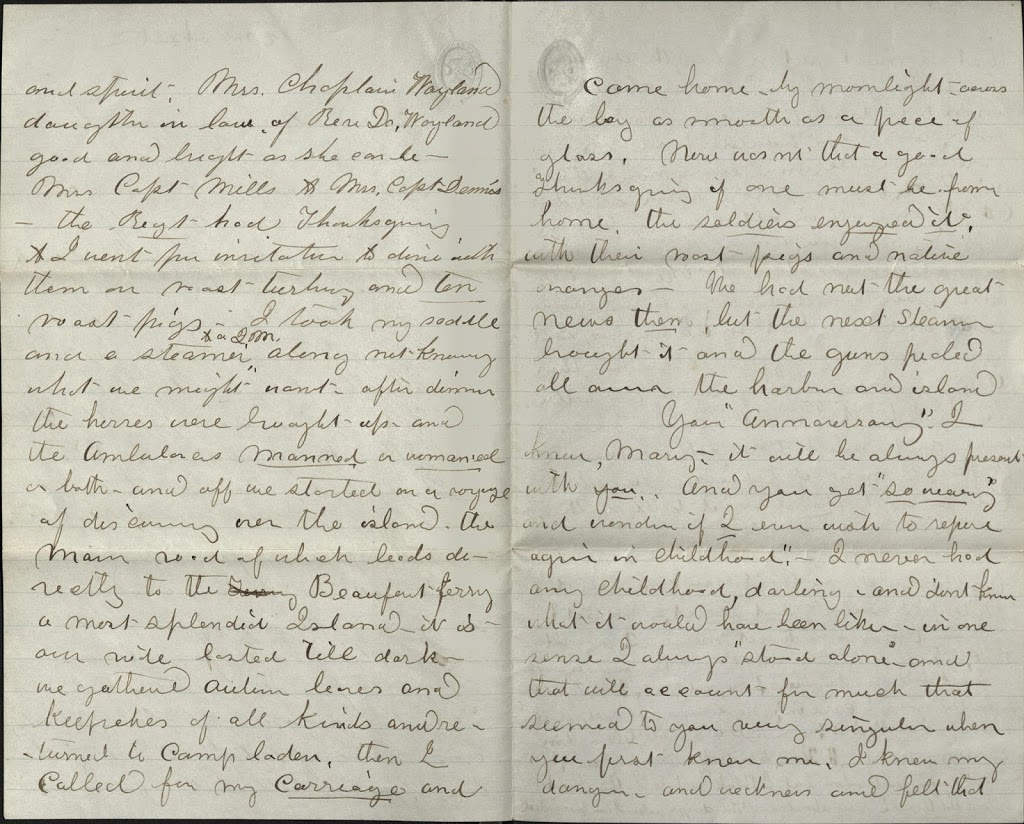

As it turned out, Clara Barton went to St. Helena Island, South Carolina to celebrate Thanksgiving Day. The Seventh Connecticut was stationed there, and Clara had become friends with several of the officers of that regiment and their wives. While the soldiers feasted on ten roasted pigs, Miss Barton and the wives enjoyed a turkey dinner. At the end of the evening, Clara journeyed home by moonlight across the bay.

HAPPY THANKSGIVING FROM OUR MUSEUM FAMILY TO YOURS!!

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Civil War Trust, “Fort Wagner: Battery Wagner, Morris Island,” accessed November 22, 2014, http://www.civilwar.org/battlefields/battery-wagner.html?tab=facts. Civil War Trust, “Lincoln’s Thanksgiving Proclamation: October 3, 1863,” accessed November 22, 2014, http://www.civilwar.org/education/history/primarysources/lincolns-thanksgiving.html. Clara Barton, Letter to Mary Norton, November 12, 1863, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University, Durham, NC. History Channel, “Abraham Lincoln and the ‘Mother of Thanksgiving,’” accessed November 22, 2014, http://www.history.com/news/abraham-lincoln-and-the-mother-of-thanksgiving. Library of Congress, “Sarah J. Hale to Abraham Lincoln, Monday September 28, 1863 (Thanksgiving),” accessed November 22, 2014, http://www.loc.gov/teachers/classroommaterials/primarysourcesets/thanksgiving/pdf/sarah_hale.pdf. National Archives, “The National Archives Celebrates Thanksgiving,” accessed November 22, 2014, http://www.archives.gov/press/press-releases/2012/nr12-29.html. PBS, “The History Kitchen: Thanksgiving, Lincoln, and Pumpkin Pudding,” accessed November 22, 2014, http://www.pbs.org/food/the-history-kitchen/thanksgiving-lincoln-and-pumpkin-pudding/. Stephen B. Oates, A Woman of Valor: Clara Barton and the Civil War, (New York: The Free Press, 1994), 173-178, 180-186, and 196-198.

Posted in: Uncategorized