Dangerous Embellishments: Women Spies in the Civil War

Nineteenth-century notions about women having chaste and guileless hearts meant that few men saw them as a threat during the Civil War. It was these perceptions about a lady’s place and capabilities that made them perfectly poised to become some of the war’s most successful spies.

Hundreds of women flirted, cajoled, and tricked men into giving up top-secret information. They wielded the era’s prejudice like weapons, using it to help win battles, save generals, and hide prisoners. Even their clothes seemed designed for smuggling secrets across enemy lines.

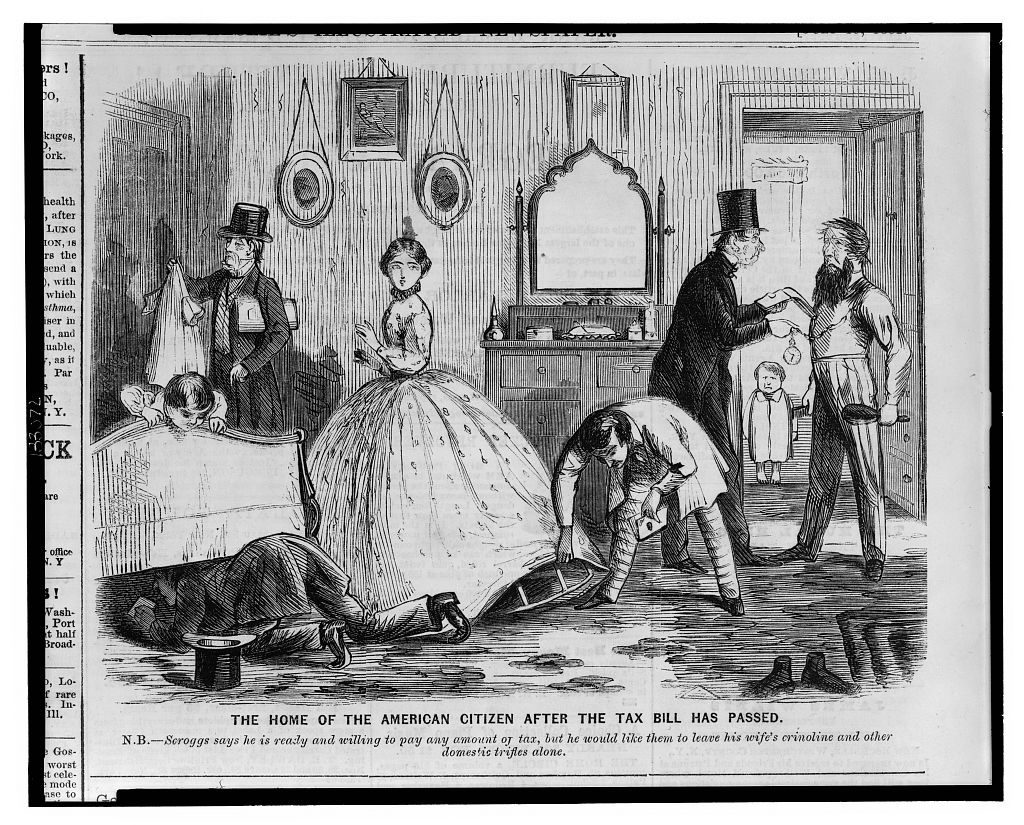

While the clothes of the era are often viewed as constricting and limiting, they provided some of the lady spy’s prime hiding places of choice. The fashionable, bell-shaped hoop skirt was held aloft by a bell-like cage called a crinoline, whose steel bands were perfect for tying things onto: from quinine and ammunition to clothes and gun parts. Their huge circumference and sturdy frames allowed for all manner of things to dangle unnoticed next to their underclothes, which meant a lady could smuggle all sorts of things over the picket lines – and did. One managed to get a bolt of cloth, several pairs of boots, sewing silk, and some packages of gilt braid across the lines in one outing. A Kentucky girl made the papers for managing to smuggle 200 Colt revolvers under her skirts over the course of two weeks.[1]

This illustration from 1862 shows how a woman’s clothes became increasingly suspect as vessels for hiding and transporting secrets, but also how men strove to protect women’s modesty, making it easier for female spies to hide secrets in their clothes. Courtesy of the Library of Congress

In Virginia, famed Confederate spy Belle Boyd brazenly snuck into Union camps at night, picked up lonely sabers and pistols, and hid them in the woods, where other girls would come along and tie the stolen goods onto their crinolines. “I had been confiscating and concealing their swords and pistols on every possible occasion,” she wrote later. “…and many an officer, looking about everywhere for the missing weapons, little dreamed who it was that had taken them.”

In an age that was so conscious of respecting a lady’s modesty, it was unlikely that a soldier on picket duty was going to do a thorough strip search. Even if he suspected a woman of carrying more than she should be, he was probably too embarrassed to say so. Confederate spy Antonia Ford sat quietly in her parlor when Union soldiers searched her house in Fairfax Court House, Virginia. When one of them asked her to stand so they could search the floor around her chair, she said, “I thought not even a Yankee would expect a Southern woman to rise for him.” The soldiers left, chastised, never knowing that she was indeed concealing important papers underneath her dress’s voluminous folds.

When Confederate sympathizer Rose O’Neal Greenhow started a spy ring in Washington, she used both her feminine charms and her clothes to great advantage. She signaled to pickets across the Potomac River in Morse code using one of her fancy fans. She flirted secrets out of Union generals and orderlies, then stitched secret letters into her corsets and the undersides of petticoats. When she learned when the Union army planned to move on Manassas before the First Battle of Bull Run, she was ready. She called over agent Bettie Duvall, aged 16, outfitted her in the clothes of a simple farm girl, and hid a small black purse in her intricate hairdo. The message inside it was simple, written in cipher: “McDowell has certainly been ordered to advance on the 16th. ROG.” Bettie rode a horse cart through Georgetown, past lines of Union tents and across the guarded Chain Bridge. No one stopped her. She arrived the next day in Vienna, Virginia, where she asked a brigadier to deliver her message to General Beauregard. When he asked to see it, she let her hair down – literally. He stood there, entranced, as the purse came tumbling down, and with it information that helped the Confederacy win the war’s first big battle.

In Washington, Confederate spy Rose O’Neal Greenhow often sewed secret messages into her petticoats, corset and underclothes to keep them from being discovered. Courtesy of the Library of Congress

Women used other domestic arts and objects to smuggle supplies and information. They cooked pistol pieces into bread leaves, packed medicine into hollow doll’s heads and jars of preserves. Laura Ratcliffe, a Confederate spy in Fairfax Court House, Virginia, smuggled thousands of dollars for famed raider John S. Mosby in the false bottom of an egg basket. Some lady spies made small holes in their eggs, sucked out their innards, and tucked messages inside their intact shells.

Down in Richmond, Virginia, the Confederate capital, Union spy Elizabeth Van Lew often used innocent-looking home goods to get information to and from prisoners of war in the city’s closely-watched jails. Under the guise of womanly Christian charity, she smuggled them books and sewing needles, which they used to prick holes in certain letters to form messages. She often brought an antique French plate warmer on her prison visits, its hollow bottom filled with secret supplies. One day, when she overheard a guard saying he was going to inspect it next time she came, she made sure to fill it with boiling water. When he grabbed it from her, it scalded his hand.

That’s not to say that spying wasn’t very dangerous for women. They fell under more and more scrutiny as the war went on. “We have to be careful and circumspect,” Elizabeth Van Lew wrote in her diary. “Wise as serpents and harmless as doves.” As more female spies were caught, it became increasingly difficult to smuggle supplies within clothing – which meant that all women who traveled in wartime had to endure aggressive search and seizure. “Women are in a bad box now,” wrote southern diarist Mary Boykin Chesnut. “All manner of things, they say, come over the border under the huge hoops now worn; so, they are ruthlessly torn off. Not legs but arms are looked for under hoop skirts, and sad to say are found.”

Endnotes and Sources

[1] To read that and other Civil War newspaper stories of women soldiers and spies click here for a compilation of them done by a grad student from the University of Texas at Tyler.

Stealing Secrets by H. Donald Winkler, Cumberland House, 2010.

Wild Rose: Rose O’Neale Greenhow, Civil War Spy by Ann Blackman, Random House, 2005.

Temptress, Soldier, Spy: Four Women Undercover in the Civil War. Karen Abbott, HarperCollins, 2014.

A Diary from Dixie by Mary Boykin Chesnut. by Isabella D. Martin and Myrta Lockett Avary. New York: D. Appleton and Company 1905, available online as a part of the UNC-CH database “Documenting the American South.”

“Women Soldiers, Spies, and Vivandieres: Articles from Civil War Newspapers” by Vicki Betts. University of Texas at Tyler, University of Texas 2016.

About the Author

Kate J. Armstrong is a writer, editor, teacher, and American history enthusiast who grew up around the District of Columbia. She has worked on illustrated nonfiction books such as National Geographic’s All Over The Map: A Cartographic Odyssey and Atlas of Beer that combine history, travel and adventure. Her podcast, The Exploress, time travels back to eras like the 19th century to explore what life was like for women of the past.

Tags: Belle Boyd, Elizabeth Van Lew, Kate Armstrong, Rose O'Neal Greenhow, Spies, Women, Women Spies, Women's History Posted in: Uncategorized