Secret Weapon

Hammond’s Secret Weapon

Thirty-three year old newly appointed Surgeon General of the Army, William A. Hammond inherited a seemingly insurmountable issue. The timely delivery to the battlefield of desperately needed medical supplies. A large part of the problem seemed to be inherent in how the military logistics system worked in 1861. Logistics, or the transportation accompanying the army hauling needed supplies, seemed logical enough. After the infantry came the artillery, the cavalry normally preceding the march and covering the rear of the army. Next in line would be ordnance, otherwise the army would be powerless. After ordnance came food for both soldiers and the heart of transportation, horses, mules and oxen. Lastly advanced medical supplies because, if the army did not conduct battle, there was little need for more than what the medical personnel could carry. At the end would be any non-government entities and army followers that may, or may not, be needed to benefit the army. Once the battle commenced with huge casualties, medical supplies became scarce within a very short time. As it became acutely evident earlier in the war, timely supply and assistance could mean the difference between life and death.

Little did the Quartermaster in command of supply depots in Washington know that one day, sitting in front of him a woman wracked by frustration and incapable of stopping a flow of tears, would be Hammond’s solution. Then-Major Daniel Rucker, after facing a day of endless appointments from all sorts of people needing or wanting something from him, was probably at his wits-end when his visitor broke down after another long day of waiting and almost certain rejection. How could he help her, he inquired. She apologized for her weak and weariness. The lady explained that all she would like was to deliver her three warehouses of supplies to needy soldiers in the field. All she needed was a pass and transportation for the goods.

Did she say three warehouses full? The army could certainly use the help. At that time, however, the bulk of the army resided just outside his office building and where ever space was available in Washington. He might be able to secure passes for her in the future, but the future was uncertain at that time. She did return home to her boarding room across town without what she waited all day to accomplish.

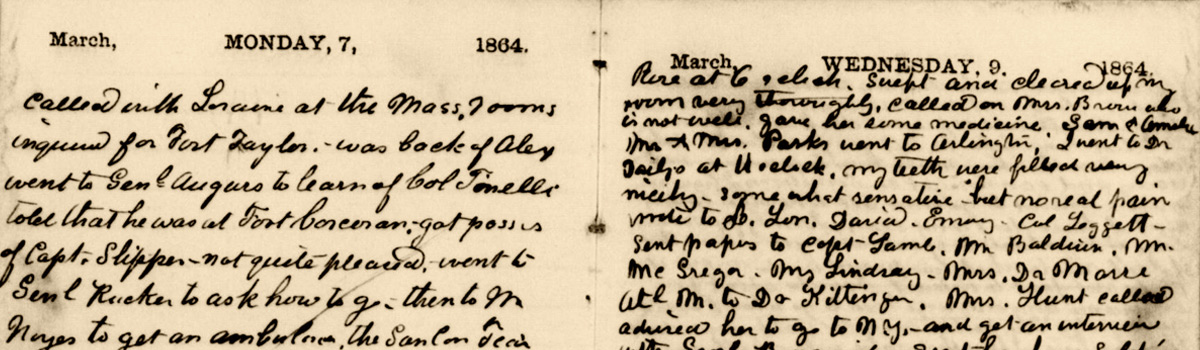

Miss Clara Barton, determined to support and contribute to the war effort in some significant way, worked then as a copyist in the Patent Office. The past Christmas she turned forty, and could not decide her role in the fraternal social system popular in the young United States of America. The role society expected her to play included marriage, bearing her husband’s children, raising them to be well educated, good Christians and contributing members of the American public. Miss Barton haughtily rejected this role for herself. She did not oppose the role for those who chose it, but thought she could contribute so much more without the responsibilities of the traditional American woman. Raised and educated as an equal to her male cousins living near the Barton homestead in Oxford, Massachusetts, she knew that she could accomplish anything they might try. She had already proven that over her entire childhood, and her family acknowledged the fact by employing her to keep the accounting books for her oldest brother’s mill. Miss Barton had tested for and received her teaching certificate at the age of seventeen and taught boys and girls in New England for eighteen years. Additionally, after moving to Washington in 1854, the Commissioner of the Patent Office employed Miss Barton, at the same pay as men, as a confidential clerk. Not only did she prove to be a very competent, she discovered a ring of thieves inside the Patent Office who had rejected patent applications and sold the patents to others for personal gain. Patent office historians would consider her employer, Judge Charles Mason, as the Commissioner best known for reform because of her work.

Miss Barton was wise enough to know that she could not accomplish much without the support of influential men and fortunately cultivated some friendships over her years in Washington. Political troubles compelled Judge Mason to leave town, but he would return later. On the top of Miss Barton’s list until 1875 stood the Honorable Senator from Massachusetts, Henry Wilson. Daniel Rucker and William Hammond would become staunch supporters as well as several officers and surgeons that accepted Barton’s assistance. Family support for her included her brother’s acceptance of a quartermaster commission in order to help keep Barton in the field. Wilson was particularly important, holding the position of Chairman of the Military Affairs committee, and frequent visitor of the White House.

After departing Rucker’s office, Miss Barton still did not fathom the importance she would play on the battlefield. Hammond and his Medical Director in the military’s largest army, the Army of the Potomac, Jonathan Letterman, as well as Rucker, would use Barton to circumvent the system. Through a cultivated “spy,” Miss Barton learned in September 1862 that McClellan expected to engage the enemy in force outside of Harpers Ferry, Virginia. Hurrying to Rucker’s office, she asked if the information was true and could she get passes. Rucker obtained passes for Barton and supplied an army wagon for transportation. The trip would be a test of Barton’s pluck, and she passed beyond Rucker’s expectations. Not only did Barton withstand the horrors of battle, she cleverly passed the army supply train during the night and camped on the battlefield the day before fighting commenced. From then on, Barton became Hammond’s secret weapon. As one officer found during the campaign, Barton knew she was not bound by army regulations to stay anywhere, or prohibited from acting without orders. During the Maryland Campaign of 1862, Barton re-supplied an estimated 17 field hospitals the day after the battle and provided lanterns for night-time surgeries. Each time she ventured to the field she improved in the quality and quantity of critically needed supplies and support.

Although they never wrote about Barton’s value as an outside player, Hammond and Rucker at least were easily intelligent enough to realize how Barton could help. Hammond’s secret weapon would help them speed up the arrival of medical supplies, but she was also an influential advocate for military medical reform. Largely through civilian pressure on Congress, the military medical system evolved from a disaster of epic proportions to the prototype for military medicine around the world. Miss Barton would go on to contribute significantly not only to her country, but internationally in promoting the permanent organization of disaster relief for victims of war and natural disasters. In the war for saving lives, score Hammond one, death zero.