Death, Immortalized: Victorian Post-Mortem Photography

Image via bbc.com

The photo above is an extended family gathered in the parlor to pose for a portrait – or is it? Photographs were increasingly becoming more affordable and accessible in the late 1850’s, but the family still put on their best clothes for the event. Upon viewing the image almost two-hundred years later, perhaps audiences today would be shocked, even horrified, to discover that the young girl asleep with her favorite teddy bear in the forefront had recently died.

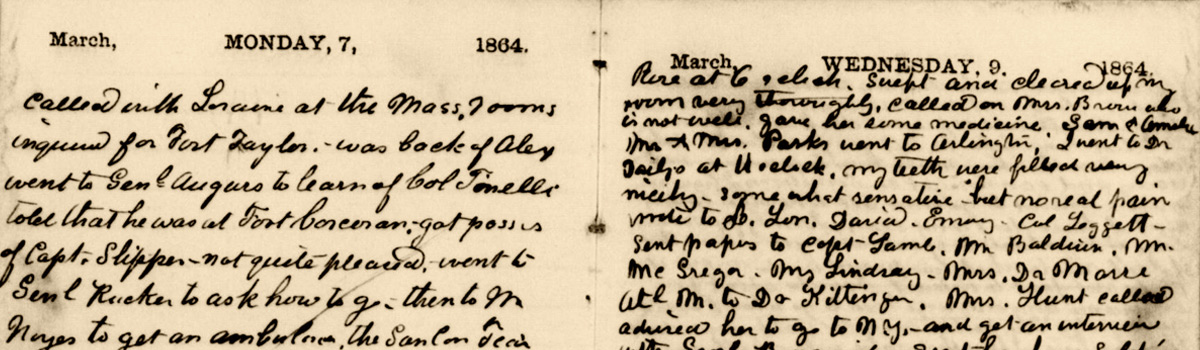

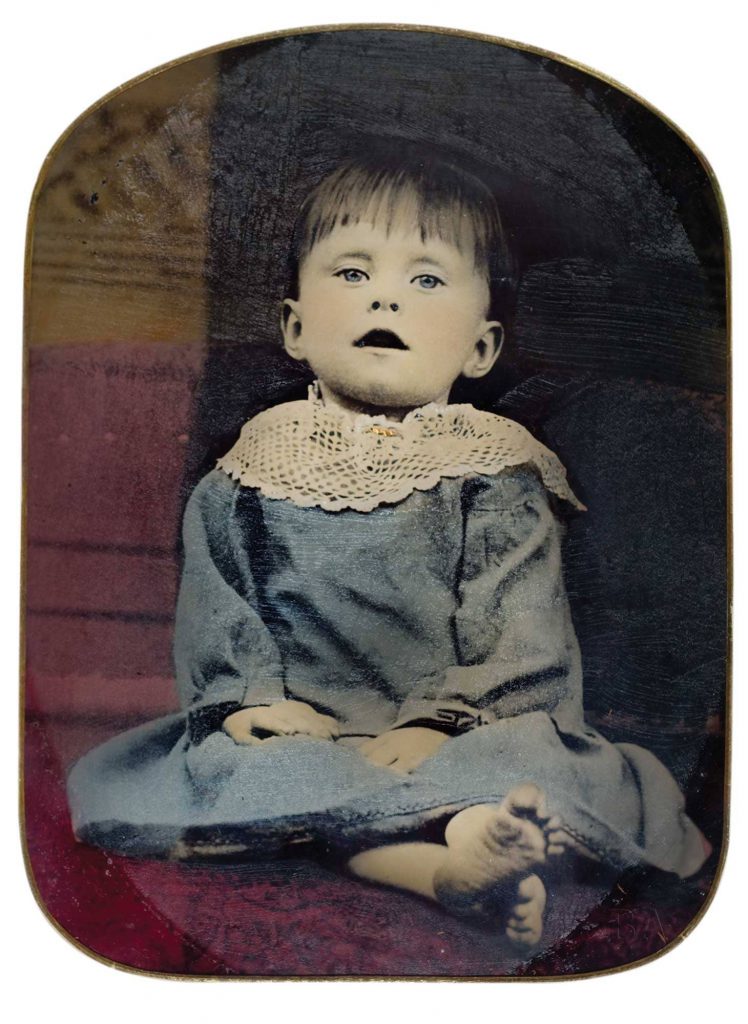

Post-mortem photography of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century is, at first glance, difficult to spot. Is a family member’s neck at a strange angle? Many are in a reclining position, slightly propped up to seem like they are supporting themselves. Do their eyes look strange? Maybe the photographer painted eyes on the image after development. Is only one figure in focus? Nineteenth-century photography required that subjects remain absolutely still, or else they would appear blurry in the picture. The deceased, of course, were very skilled at remaining still for portraits.

This child’s eyes are hand-painted open on tintype, circa 1870. Image via Burns Archive via HIstory.com

Americans in the 1800s were far more intimately acquainted with death than we are today. Most of this was out of necessity–before embalming procedures became popularized, it was the duty of the family to quickly prepare the body for a viewing and burial. Families would typically hold viewings in their own parlors at home, a tradition that later gave funeral parlors their name. The birth of the funeral industry in the early twentieth century and the growth of large, sanitized hospitals brought about a shift in the way Americans interacted with death.

This intimacy with death and dead bodies was closely connected to the growing commercialization of Victorian mourning culture. First popularized by Queen Victoria’s insistence upon wearing black for the rest of her life following the death of her husband Prince Albert, the English and eventually Americans began buying and selling clothing, accessories, and stationery specifically for the mourning period culturally required after the death of a loved one. The widespread nature of miscarriages and diseases such as typhoid and dysentery guaranteed that mourning materials remained in demand.

The presence of a dead relative in the family photo is not the only aspect of Victorian death culture that would cause many to shudder in discomfort today. Many carried their loved ones’ locks of hair, and even more had this hair made into jewelry or woven with other strands to make a family hair wreath. This was considered “sentimental jewelry,” with the understanding that they could keep a concrete, physical, and timeless piece of their loved one with them even after death.

In this portrait, the entire class was involved in mourning their classmate. Circa 1910 from the Burns Archive via History.com

Post-mortem photography similarly allowed for the family to keep a reminder of their loved one’s visage. Though the development of early photography dramatically lowered the price of portraits, the entire affair was still rather expensive, and thus often few pictures existed of children unless one’s death brought the family together. For this reason, large family photos often are centered around a child in the forefront, surrounded by flowers. This picture is the last chance the family will have to see their child’s likeness.

Though in some post-mortem photos it may take a minute to identify the deceased, the majority of subjects are depicted as if asleep. This removes much of the difficulty for the photographer–he does not have to pose the deceased or paint the eyes open during development. This also lends itself well to a popular Victorian belief of “The Last Sleep” and “A Good Death,” in which death is a peaceful process that leads the loved one to a benevolent afterlife. Gone are the “memento moris,” or fearful reminders that death is near, of the eighteenth century. These were often meant to remind Christians to abstain from sin, as the afterlife could come at any moment. By the nineteenth century, however, the Christian god was viewed as far more benevolent than previously depicted in “fire and brimstone” speeches about hellfire and God’s wrath. In the 1800s, the child mortality rate was so high that parents had to believe that their child had moved on to a better place in heaven. Their restful repose in post-mortem photography reflects this belief in a peaceful afterlife.

Today, Victorian mourning practices seem excessively morbid, even macabre. A greater understanding of the meanings behind practices such as post-mortem photography, however, allows a modern viewer to see an image for what it was: a comforting reminder that a loved one was merely “at rest” and waiting for a heavenly reunion.

About the Author

Melissa DeVelvis is a doctoral student in history at the University of South Carolina, specializing in the Civil War era, gender studies, and sensory and emotions history. She is currently processing and archiving the collection of Bishop John Hurst Adams for the South Caroliniana Library and is a part-time site interpreter for Historic Columbia.

Tags: 1800's, Good Death, Melissa DeVelvis, Photography, Post-Mortem Photography, Victorian, Victorian Death Culture Posted in: Uncategorized