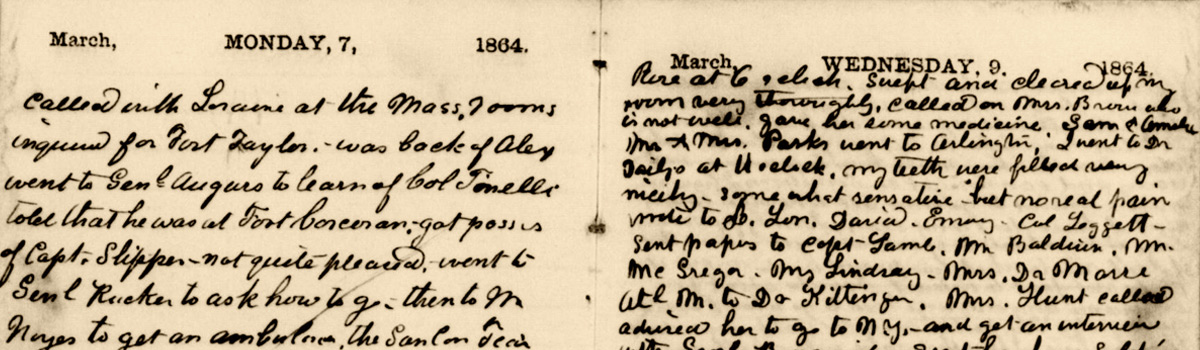

Photographs of the Dead at Antietam

The American Civil War was not only a political and cultural turning point but also the first American conflict to be documented by photographers. For the first time civilians were able to see the horrors of the modern battlefield without leaving the safety of their own community. With more than 620,000 deaths, the Civil War became the largest and most devastating war ever fought on American soil. On a single bloody day during the conflict, more than 3,600 soldiers fell dead on the banks of Antietam Creek in western Maryland. That day marked a turning point in how Americans looked at warfare. September 17, 1862 was a day marked by bloodshed, loss, and it left behind a remarkable photographic legacy.

The Battle of Antietam was eloquently recorded, both by the soldiers who experienced the battle, and by the photographers who arrived after the shooting stopped. While photographic images provide a different perspective than eyewitness accounts, the images were a startling documentation of what most civilians would never see themselves. In this era, most Americans were rapidly being exposed to photography, and the integrity of photographs went largely unquestioned. Images of the dead were deeply disturbing in a way that Americans were not accustomed to, and these photographs greatly contributed to shifting the dialogue surrounding the war.

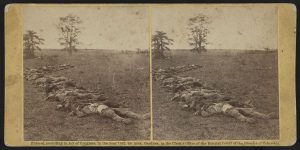

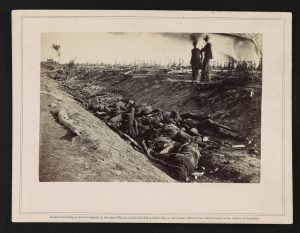

Confederate dead collected for burial (Courtesy of the Library of Congress)

In the days after the battle, burial details came to collect the dead. The immense volume of bodies and destruction became a horrible burden for those forced to reckon with it. Thousands of corpses lay lifeless and still, left to settle into the dirt of the fields. Walking among those digging graves and moving bodies was Alexander Gardner and his assistant James Gibson. Both men worked closely with renowned New York photographer, Mathew Brady, who owned a famous gallery in New York City. In the weeks following the Battle of Antietam, thousands of curious New Yorkers flocked to Brady’s studio to see the scenes captured by Gardner and Gibson.

Gardner arrived on the battlefield on September 19, just two days after the battle had ended. Gardner was not bashful in his intentions: he walked amongst the dead and the living who handled them, not shying away from those who had grisly wounds, who fell over rocks in their final moments, and who bloated under the September sun as their bodies returned to the earth. The images captured by Gardner and Gibson were unlike anything the public had seen before.

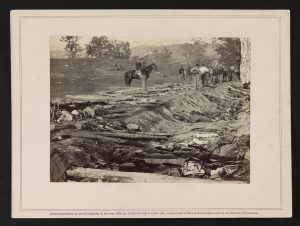

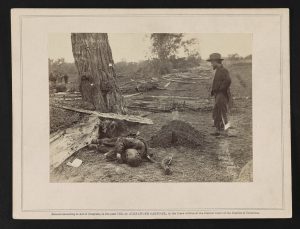

The destruction in and around Antietam’s bloody lane (Courtesy of the Library of Congress)

Gardner chose to use new photographic technologies during his trip to the battlefield: albumen and the stereograph. Albumen photographs rely on egg whites to join the photographic chemicals to paper, and have a silvery or almost sepia tone to them. The stereograph, however, provided a different, more immersive experience. It placed two nearly identical photos next to each other to be looked at in concert with device known as a stereoscope. Using this technique, the image appeared nearly three-dimensional, and with very crisp detail. Some stereograph photos were even hand tinted with color, in order to create a more realistic depiction of the scene. The photographs could also be displayed on their own as large, photographic prints, similar to those that we might see in a photography studio or museum today.

Dead soldiers in Antietam’s infamous bloody lane (Courtesy of the Library of Congress)

The photographs were originally displayed in the gallery space for all of New York to see. Many photographs in this body of work openly depict the grim realities of battle: fallen soldiers lay in a ditch and await burial while a member of the burial detail looks over the scene, sitting tall on a horse. While many photographs attempt to label if Confederate or Union soldiers were depicted in its frame, the dead were often intertwined just as they had fallen. The photographs do not glamorize war, but allow the viewer to imagine that the dead they are looking at could be their loved ones. Every mother who lost a son, husband, or brother in battle could look upon Gardner’s photographs and imagine that the anonymous soldier in front of her eyes was her loved one. Gardner provided a body of work that not only documented the horrors of war for the first time in American history, but also provided a relic for a nation in mourning.

Even the newspapers were responding: The New York Times wrote that the photographs “bring home to us the terrible reality and earnestness of war. If [Gardner] has not brought bodies and laid them in our door-yards and along streets, he has done something very like it…”[1] Since photographs could not yet be reproduced in newspapers, delicate wood etchings were created to further distribute the horrific Antietam shots, depicting details of the dead strewn about the landscape. These images and illustrations traveled traveled across the country and into the homes of those who had never been exposed to grisly realities of war.

A buried Union soldier and an unburied Confederate soldier near the West Woods at Antietam (Courtesy of the Library of Congress)

These images brought Americans together in revulsion. The Battle of Antietam touched the lives of thousands, if not millions of Americans, and photographs of the unburied dead drove a nation into mourning. Everyone knew someone who had lost someone, whether they died fighting, from battle wounds or infection. The Gardner images had such power because they were new and startling; this impact contributed to a shift in how Americans quite literally viewed the war.

The photographs taken in the days following the Battle of Antietam have a lasting legacy that remains with us today. They serve as monuments to the lives lost in the Civil War, anonymous young men with faces twisted and distorted by pain and the ravages of decomposition that serve to represent the loss of hundreds of thousands of Americans. Held by the Library of Congress, Gardner’s photographic work serves not only as the first photographic documentation of battle on American soil, they are also in conversation with contemporary photographs of war that Americans view every day online, in newspapers, galleries, and museums across the United States.

Footnotes

[1] “Photography at Antietam.” National Parks Service. Accessed August 21, 2017. https://www.nps.gov/anti/learn/historyculture/photography.htm.