Seeking Asylum

A Story of Reconstruction, Race, and Mental Health

In the first report issued by Virginia’s Central Lunatic Asylum for Colored Insane in 1870, patient Georgiana Page is described as a “useless old harlot.” While terms such as “idiot” and “moron” to describe mental patients were used frequently, the demeaning language used here is unusually shocking to read. However, the Central Lunatic Asylum itself was not a usual institution. According to one of it’s later Superintendents it was the first hospital of its kind in the world, the first mental institution founded solely for the care of African American patients.[1] Georgiana was one of 252 patients residing in the hospital at the time of the report, alongside “Useless” Samuel Moseley, “very useful” Lucy Carrington. When the state of Virginia’s Central Lunatic Asylum opened its doors, it was the culmination of over two decades of effort to secure care for Virginia’s mentally ill African American population.[2]

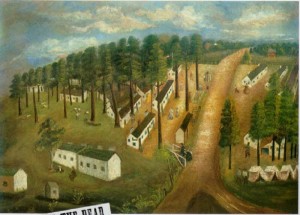

Painting of Howards Grove Hospital in Richmond, VA by an unknown Confederate soldier, Courtesy of Family Search

Virginia’s Central Lunatic Asylum for Colored Insane is believed to be the world’s first mental health institution solely for African Americans, but it did not start out that way. It first opened its doors on June 13, 1862 as a Confederate war hospital: Howard’s Grove. Like the majority of wartime hospitals, it consisted of single story wooden structures.[3] Five months later, a separate hospital dedicated to the treatment of African Americans with small pox was built directly adjacent to Howard’s Grove. The two hospitals functioned side by side for two years until 1864, when the smallpox hospital became a part of Howard’s Grove.[4]

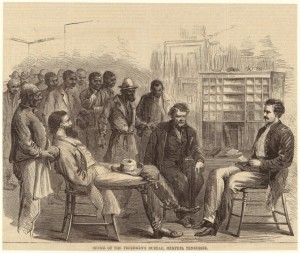

When the Union Army captured Richmond in April 1865 the facility became part of the Freedmen’s Bureau[5]. Established in 1865, the Freedmen’s Bureau assisted former slaves adjusting to freedom.[6] Commissioner Oliver Otis Howard created the Medical Division of the Bureau in June of 1865 to serve the vast number of freedmen who were often refused care at established hospitals.[7] Most hospitals run by the Freedmen’s Bureau were intended to be temporary, often located in converted structures such as schools and almshouses. One Freedmen’s doctor in Savannah, GA, wrote to request new facilities, complaining that the “shanties” in present use were “utterly unfit for human beings”.[8] The Freedmen’s Bureau took special pains to avoid taking in the mentally ill, and encouraged mental health institutions to take on the patients instead. The Freedmen’s Bureau believed that the mentally ill would disrupt the other patients. However, local mental health institutions also refused to treat these patients, due to their race. The Civil Rights Act of 1866 required state run mental institutions to accept African American patients, but despite this, a number of hospital superintendents openly refused, leaving a number of mentally ill African Americans with nowhere to go.[9]

The idea of founding an institution in Virginia solely for the treatment of mentally ill African Americans had been discussed as early as 1844, long before the Civil War. Dr. Francis T. Stribling, the Superintendent of the Western State Lunatic Asylum in Staunton, VA, suggested that an asylum for the “negro insane” should be established by the state.[10] Beginning in 1846 the majority of mentally ill African Americans in Virginia were cared for in the Eastern Lunatic Asylum in Williamsburg, where they were primarily housed in the basement after all white patients had been accommodated. Dr. John Galt, the Superintendent of the Eastern Lunatic Asylum, also believed that an asylum dedicated solely to the care of African Americans should be built.[11]

Finally, nearly 25 years after Dr. Stribbling’s first suggestion, in December of 1869, the State of Virginia established a dedicated mental institution solely for the care of African American patients. Howard’s Grove was transferred from the Freedmen’s Bureau into the control of the State to become the home of this new institution, now known as the Central Lunatic Asylum for the Colored Insane. “The necessity of a separate asylum for this unfortunate class is, we think, generally acknowledged by all who have seriously considered the subject” proclaimed the asylum’s board president, Hunter McGuire.[12] Although establishing an African-American only mental institution was unique for 1869, transferring patients from the care of the Freedmen’s Bureau to state care was not. The closing of Freedmen’s Hospitals and transfer of patients to state care took place on a national scale from the late 1860s into the early 1870s. The Freedmen’s Bureau itself was closed in 1872, having lasted a scant seven years.[13] In the case of the Central Lunatic Asylum for the Colored Insane (formerly Howard’s Grove), the Freedmen’s Bureau paid the hospitals expenses through February 1870.[14] The state removed any patient who was not deemed insane, while all of the African American patients at the Eastern Lunatic Asylum were transferred to the Central Lunatic Asylum, as well as any mentally ill African American who was incarcerated in a Virginia jail.[15]

The war hospital turned temporary Freedman’s hospital turned asylum was not prepared for its occupants. One of the hospital’s first superintendents, D.B. Conrad, described it “as crude as could be.”[16] The current facility was comprised of “a few old wooden shanties” with distant, isolated washrooms and no sewerage system.[17] With no dedicated dining rooms, patients ate their meals on the ward floors or in their beds. A number of improvements, including additional structures for dining rooms, an infirmary, and new bathrooms, were quickly undertaken.

The care and expense taken in its renovation, as well as its status as one of the first insane asylums exclusively for mentally ill African Americans might lead one to believe that Central Lunatic Asylum for the Colored Insane was a model institution. However, racism still shaped the treatment of and attitude towards its patients. This is evident in the list of patients that appears in the 1870 hospital report. In addition to the “old harlot”, the report contains a record of a patient named Godfrey Goffney who “attempts to kill every white man.” The supposed cause of his psychosis, along with that of several other patients, is listed as “freedom.” Patient Rose Warren “Will not work now free.” [18] Caleb Burton, who fancied himself on a “mission to free the world”, suffered from “delusional insanity” stemming from “freedom-result of war.” This depiction of freedom as the cause for patient’s maladies is clearly intended as an indictment of emancipation.[19] This is consistent with attitudes towards emancipation and slavery held in the south before the war.

An article appearing in the American Journal of the Medical Sciences by Edward Jarvis in 1844 noted that insanity, according to the sixth census of the United States, appeared to be much more prevalent in free African Americans than in slaves.[20] Jarvis points out a number of errors in the census, including vast underestimations of the number of insane and one institution in particular where the entirely white population was listed as black.[21] Drapetomania, a theoretical illness that was supposed to cause slaves to run away, is highly apparent in the “grossly erroneous inferences” drawn by the census.[22] The belief expressed by Vice President of the Confederacy Alexander Stephens that slavery was the “natural and normal condition” of African Americans continued well after emancipation.

One of the primary evaluations of a patient at the hospital during this time was how useful they were. Samuel Mosely is listed as “useless”, Lucy Carrington is “very useful”, and John Boyd “learned to work.” These repeated references to a patient’s usefulness or lack thereof are telling.[23] One of the primary, albeit unstated, functions of the Freedmen’s Bureau was to create a labor force from the vast number of freed African Americans.[24] “The government became interested in the health conditions of freed slaves because it wanted to create a healthy labor force,” explains Dr. Jim Downs, “When the federal government eventually responded by creating the Freedmen’s Bureau in 1865 and subsequently developing a system of medical care for former slaves through the South, ideas about freed people’s labor power shaped the terms of the policy.”[25] Over half of the patients with detailed remarks in the report are described solely in terms of their ability to work.

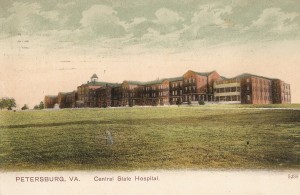

The rapid growth of the patient population at the Central Lunatic Asylum made “speedy action… in providing a permanent and sufficiently large asylum for the care of these unfortunates” necessary.[26] In 1882, a large tract of land was procured near Petersburg, and construction on a permanent home for the institution was begun.[27] The main building was designed to the Kirkbride Plan, which was the standard form of construction for insane asylums during the second half of the 19th century. Construction was completed in 1885 and all patients were transferred that March.[28] In 1894 the name of the asylum was changed again, this time to Central State Hospital to “conform to modern ideas.”[29]

Residents of Central State Hospital playing Field Sports in 1910. Image Courtesy of Asylum Projects.

The end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century saw rapid patient population growth and a tremendous amount of expansion. This was not limited to Central State Hospital. Several other state mental institutions founded specifically for the treatment of African Americans were constructed, including Crownsville State Hospital in Maryland, Goldsboro State Hospital in North Carolina, and Lakin State Hospital in West Virginia.

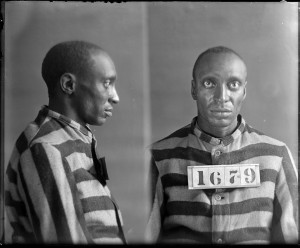

Hiram Steele was a patient at Central State Hospital several times throughout his life. He was first convicted of a crime (hence the mug shot), then found insane and sent to the asylum. He would spend most of his life either in Central State Hospital or in prison. Photograph courtesy of the Library of Virginia.

Central State Hospital remained a segregated institution until the Civil Rights Act of 1964, when it began to admit patients of all races. The size of the institution has declined sharply since its peak in the 1950s. Although the main building was demolished years ago, the hospital remains an active facility to this day. It is, along with the Howard University Hospital in Washington D.C., originally known as the Freedmen’s Hospital, one of the last vestiges of the Freedmen’s Bureau Medical Division.

About the Author

Craig Swenson holds a Bachelor’s Degree in history from the University of Baltimore and currently completing his Master’s Degree in Museum Studies at the Harvard University Extension School. His research deals with medical and architectural history with a focus on mental health. He is currently employed at the National Building Museum where he most recently worked on The Architecture of an Asylum, an exhibition on St. Elizabeth’s Hospital. He is also an intern at the National Museum of Civil War Medicine.

Works Consulted

- “All the Hospitals”. Richmond Whig. 10 April 1865.

- “City Small-pox Hospital for Negroes”. Richmond Dispatch. 12 January 1863

- Drewry, William Francis. Historical Sketch of Central State Hospital. Everett Waddey CO. 1905.

- Jarvis, Edward. “Insanity Among the Coloured Population of the Free States”. The American Journal of Medical Sciences. Volume 7. January 1844. Pages 71-83

- Report of the Board of Directors and Medical Superintendent of the Central Lunatic Asylum. 1870.

- Report of the Board of Directors and of the Superintendent of the Western State Hospital of Virginia. 1848. Accession 31030, State Government Records Collection, Library of Virginia, Richmond, Virginia.

- Wm. A. Carrington to Surgeon General Moore. 3 May 1864. National Archives RG 109 Ch. 6, Vol. 364.

- Calcutta, Rebecca Barbour. Richmond‘s Wartime Hospitals. Pelican Publishing Company, 2005.

- Downs, Jim. Sick From Freedom Oxford University Press, 2012.

Endnotes

[1] Drewry, William Francis. Historical Sketch of Central State Hospital. (Everett Waddey CO. 1905). 2

[2] Report of the Board of Directors and Medical Superintendent of the Central Lunatic Asylum. General Tabular Statement. (1870)

[3] Calcutt, Rebecca Barbour. Richmond’s Wartime Hospitals. (Pelican Publishing Company, 2005) 159

[4] Wm. A Carrington to Surgeon General Moore. 3 May 1864. National Archives RG-109 Ch. 6 Vol. 364.

[5] Drewry, Historical, 2

[6] Downs, Jim. Sick From Freedom. (Oxford University Press, 2012), 45

[7] Downs, Sick, 71

[8] Downs, Sick, 71

[9] Downs, Sick, 146-7

[10] Report of the Board of Directors and of the Superintendent of the Western State Hospital of Virginia. (1848) Accession 31030, State Government Records Collection, Library of Virginia, Richmond, Virginia.

[11] Drewry, Historical, 1

[12] Report… Central. 6

[13] Downs, Sick, 154-5

[14] Drewry, Historical, 2

[15] Drewry, Historical, 2

[16] Drewry, Historical, 2

[17] Drewry, Historical, 4

[18] Report…Central. 6

[19] Report… Central. General Tabular Statement

[20] Jarvis, Edward. “Insanity Among the Coloured Population of the Free States.” The American Journal of Medical Sciences. Volume 7. (January 1844) 74

[21] Jarvis, Insanity, 75

[22] Jarvis, Insanity, 82

[23] Report… Central. General Tabular Statement.

[24] Downs, Sick, 58

[25] Downs, Sick, 45-47.

[26] Report… Central. 8

[27] Drewry, Historical, 8

[28] Drewry, Historical, 9

[29] Drewry, Historical, 13

Tags: African American History, Asylum, Black History, Central State Lunatic Asylum, Craig Swenson, Freedmen's Bureau, Mental Health, Reconstruction Posted in: Uncategorized