Artifact Series – Bayonet

|

| Bayonet found in the attic of the CBMSO Property of U.S. General Services Administration |

This is a bayonet from an 1853 Enfield rifle, one of the most common rifles used during the American Civil War. A bayonet, though designed to act as a spear blade, had many uses outside of combat. Soldiers during the Civil War would use their bayonets, especially ones like this, as candleholders, cooking utensils, and much more.

|

| Detail of bayonet socket Property of U.S. General Services Administration |

This bayonet in particular may have been used for something outside of combat, as indicated by the bend in the blade, and a few missing pieces on the socket. It was found among the artifacts in the attic of 437 7th Street NW, Washington DC, and might make it into the exhibits once we start installing them.

Now, why would Clara Barton – or anyone who was living in the boardinghouse – have a bayonet? There are a couple possible answers to that question, one of which we find extremely exciting.

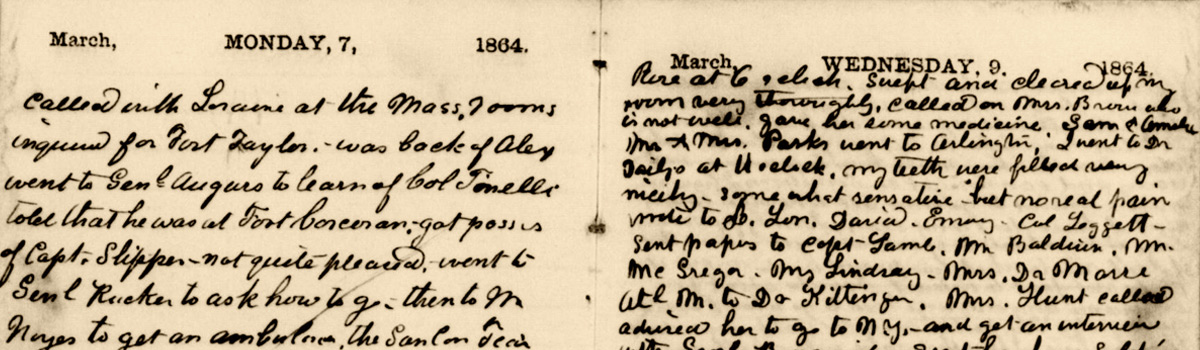

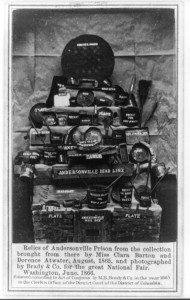

After the end of the Civil War, Clara was approached by a young man named Dorence Atwater. He had been a Union prisoner at the Confederate prison in Andersonville, Georgia, and had managed to make a list of the dead, which he then smuggled out of the prison after his release. Clara, Dorence, and a number of other people traveled down to Andersonville to identify the graves of the soldiers there, using Atwater’s Death Register as their guide.

|

| Courtesy of the Library of Congress |

While there, Clara collected a number of items from Andersonville that she would use in her advertising campaigns. She called those her Andersonville Relics.

There are no bayonets in that picture, but Clara did collect several. One of her close friends, famous women’s suffragist Frances Dana Gage, wrote a letter in 1866 to the New York Independent to help Clara advertise for the Missing Soldiers Office. In that letter, Gage describes some of the artifacts, including a number of bayonets. “These bayonets,” she says, “were picked up in that Golgotha…”

We currently have no idea where the Andersonville Relics officially are. There is, however, a very distinct possibility that our 1853 Enfield bayonet is one of them.

We are all very excited by the thought of having this artifact on display at the CBMSO in DC, but it simply won’t be safe to do so until we can get our security system installed. If you want to see this artifact, as well as the others you’ll be seeing on this blog in the future, please consider donating to this unique portion of Clara Barton’s history.

Until next week!

Posted in: Uncategorized