“Ready for Mischief”

Dr. Mary Walker and her Service during the Civil War

Dr. Mary Walker, 1865. Photo by Matthew Brady. Courtesy of National Archives.

At the outbreak of the American Civil War, men across the country stepped forward to serve in the military and were celebrated by their communities for demonstrating their bravery. Though the majority of men who served had no training or fighting experience, they were enlisted without question by grateful governments and marked as heroes for their selflessness. Unfortunately, women who stepped forward to serve and support the military were not so lucky in their reception.

Many women were eager to work as nurses and caretakers during the war, but endured opposition from male leaders and scorn from their communities. However, faced with persistent lobbying and intensifying bloodshed, military leaders soon allowed women to serve as nurses. Though they were allowed to serve, female nurses were still expected to live by traditional gender norms of the nineteenth century. While most women navigated the war effort and found gender-appropriate work for themselves, Dr. Mary E. Walker of New York embarked on a crusade to become a surgeon in the Union Army.

Dr. Walker was twenty-eight years old at the outbreak of Civil War and an accomplished doctor. She was the second woman in the country to have earned her medical degree and operated her own practice in Rome, New York. In October 1861 Dr. Walker made her way to Washington D.C. in search of work in one of the many hospitals there. She found work as an assistant surgeon at a hospital inside the US Patent Office, but she was never formally hired or paid. Though she took satisfaction with her work, Dr. Walker was unable to support herself without a wage and left Washington in early 1862.

Medical kit used by Dr. Mary Walker. Courtesy of the National Museum of Health and Medicine

By November 1862, Dr. Walker was ready to head back to Washington. When she heard the army was camped in Warrenton, Virginia, Dr. Walker bypassed the Capitol and traveled directly to the front. She arrived in the midst of a severe typhoid epidemic and immediately set to work caring for the men. Soldiers noted her tireless efforts to treat the men, as well as her unusual appearance. Dr. Walker had taken to wearing trousers and a military jacket for practicality and comfort. Her startling appearance left a lasting impression on the soldiers she treated. She would continue to wear “man’s” clothing for the rest of her life.

Dr. Walker was put in charge of transporting men back to Washington and ensuring they received treatment upon their arrival. She was praised for her compassionate care and started garnering interest among leaders in Washington for her skill as a surgeon.

Almost immediately after Dr. Walker moved soldiers to Washington, the Union Army began the fateful Fredericksburg Campaign, which culminated in the bloody and mismatched fight on December 13th, 1862. Dr. Walker quickly traveled to the battlefield and set to work triaging and treating the wounded retreating across the Rappahannock River.

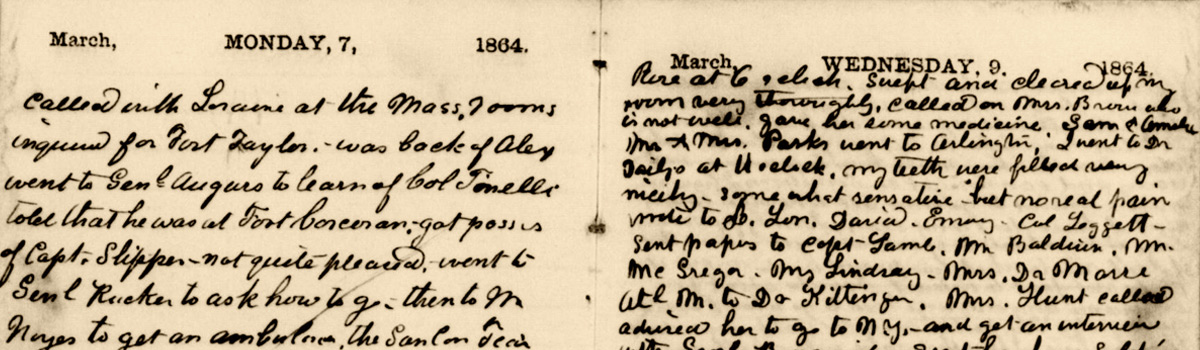

Treating soldiers in the aftermath of the battle of Fredericksburg was the first time Dr. Walker worked on the front lines. If the shrieking, groaning, bleeding and dying men unnerved her, Dr. Walker did not reveal this in her writings of the day. Though her written recollections of Fredericksburg are brief, they are incredibly vivid.

Dr. Walker worked somewhere on the grounds of the Lacy House (today known as Chatham), likely close to Union pontoon river crossing just north of the house. She examined soldiers, noting which ones should be sent to Washington and which should be treated immediately on-site. She gave orders to stretcher-bearers on how soldiers should be handled in order to prevent pain and discomfort. She spoke with such authority that her commands were obeyed.

The Lacy House (today known as Chatham Manor). Courtesy of Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania NMB

During her brief time in Union Army hospitals, Dr. Walker had seen serious wounds and illnesses, but her time on the front lines in Fredericksburg exposed her to horrific injuries. She noted one particular case of a soldier with a grievous head injury:

“…a shell had taken part of his skull away, about as large a piece as a dollar…I could see the pulsation of the brain, and when he talked I could see a movement of the same, slight though it was. He was perfectly sensible, and although I never saw him after he was taken to Washington, I learned that he lived several days.”

Dr. Walker’s exposure to battle at Fredericksburg did nothing to dissuade her from working for the Union Army; rather it fueled her ambition to receive an official commission as a US Army surgeon. She lobbied generals and politicians persistently, and her efforts were rewarded in 1864, when she was commissioned and assigned to the Army of the Cumberland.

Dr. Mary Walker in 1870. Courtesy of the Oswego Historical Society

Despite this achievement, Dr. Walker faced obstacles and harassment at every turn. Generals and doctors refused to work with her. Rumors were spread that she was a prostitute. She was captured while in Georgia and sent to a prison in Richmond. Adding insult to injury, Confederate newspapers reported rumors that she took prison guards as lovers until her release in August 1864.

After the war ended, Dr. Mary Walker was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor for her services to the US Army. Unfortunately in 1917, her award was rescinded, but Dr. Walker refused to return the medal and wore it proudly until her death in 1919. Dr. Walker’s medal was posthumously restored. She remains the only woman to have earned this prestigious decoration.

Further Reading

- Graf, Mercedes. A Woman of Honor: Dr. Mary E. Walker and the Civil War. Gettysburg: Thomas Publications, 2001.

- Snyder, Charles McCool. Dr. Mary Walker: The Little Lady in Pants. New York: Arno Press, 1974.

- Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park

Maureen Lavelle hails from Boise, Idaho and is a current graduate student at West Virginia University. Her studies include Public History and women’s memorialization efforts in the postwar South. She studied U.S. History at Willamette University, and spends her summers working as a seasonal at Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park.

Tags: Fredericksburg, Mary Walker, Maureen Lavelle, Women's History Posted in: Uncategorized