The First Modern Thanksgiving in Washington, D.C. and Beyond

Massachusetts has an undisputed claim on Thanksgiving. The story of the Mayflower, early America’s tough start, and the meal shared between Native Americans and Pilgrims in 1621 is part of our national identity. But Washington, D.C. deserves some credit for the holiday too. For it was here, in an attempt to lift the spirit of the public in the third year of the Civil War, that the holiday as we know it was born.

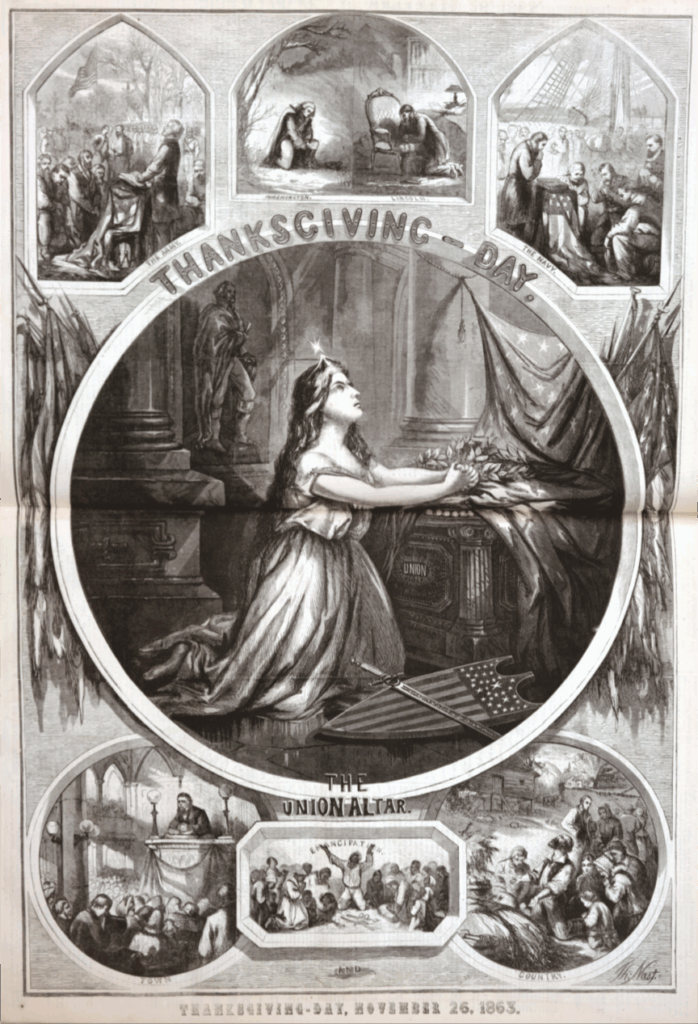

Thanksgiving-Day (Gilder Lehrman)

Abraham Lincoln’s October 1863 proclamation to make the last Thursday of November an annual Thanksgiving created the modern holiday. Sarah Josepha Hale, who had championed a national Thanksgiving holiday for decades in her magazine Godey’s Lady’s Book, won Lincoln over. Other days of Thanksgiving had previously been held in America. Typically, they would be declared to honor national achievements, but those were meant to be one-off events. Lincoln broke the trend, and the first modern Thanksgiving was held on November 26, 1863. In 1865, Andrew Johnson moved the holiday to the first Thursday of December. That change, like many things from Johnson’s presidency, did not stand the test of time. By 1866, the holiday reverted back to the last Thursday of November. In 1870, Congress voted to make Lincoln’s version of Thanksgiving an official federal holiday.

The Washington-based Daily National Intelligencer, a Republican leaning paper, ran the following message for its inaugural 1863 Thanksgiving issue:

The People of the Loyal States are this day summoned, by invitation of the President of the United States, to return thanks to Almighty God for the mercies and blessings which have crowned the present year.

It is a signal mark of the Divine benignity towards this nation that, while it is rent and torn by the conflicting passions of men, the good hand of the Great All Father has none the less been laid upon it in kindness and forbearance. It is because His bounty has failed not, and His compassions are not removed from us, in the face of our ill-desert, that we this day are permitted to rejoice . . . .

Preparations had been made for Thanksgiving for the wounded and sick in Washington’s hospitals. Nurse Amanda Akin Stearns of Armory Square, the city’s largest hospital, wrote in her diary on November 25, 1863, that special rations were delivered for the patients’ feast on the 26th. These included donated delicacies like oysters and cranberries courtesy of the New York Relief Society.

Amanda Akin Stearns (National Museum of American History)

On Thanksgiving Day, she wrote:

The unclouded sky and exhilarating atmosphere were types of the sunshine and joy in hearts made glad by a holiday. Our soldiers seemed to enjoy their freedom and the good things prepared for them, and as that is the one especial object to which we are devoting ourselves at this time, we were happy too.

We also had a fine dinner for which we were thankful, not having fared very sumptuously of late; Dr. Alcan, having kindly remembered us by sending some of his nice French cordial with his compliments, we made ourselves quite merry with toasts . . .

The band of music I enjoyed exceedingly—it was just the sunset hour. . . . Sister Southwick presented me with “Hospital Sketches,” by Louisa M .Alcott; Miss Marsh treated us with Boston mince pie at the“ Chateau” in the evening, over which we gossiped a while before retiring.

Across the Potomac River, in Alexandria, Virginia, New York abolitionist Julia Wilbur took a break from volunteering in the city’s contraband camps to enjoy the holiday. She had distributed goods the days prior to ensure self-emancipated individuals could celebrate too.

Julia Wilbur (Wikimedia)

Julia spent most of her day with the city’s top ranking civil and military authorities. Before having a turkey dinner with General Christopher Augur’s family, she attended a rally. After dinner she went to see Colored Masons Lodge #2 lay the cornerstone for Bethel Church.

Two of Washington’s most famous nurses were out of town. Clara Barton was stationed hundreds of miles away. She spent the day on St. Helena Island, South Carolina. Her confidant Frances Gage and brother David both left for the north weeks prior, but Clara always had friends among grateful soldiers. She traveled in the morning by boat to the camp of the 7th Connecticut. She spent the entire day with them. The dinner for the regiment consisted of 10 whole pigs roasted for enlisted men to enjoy. The highest ranked officers, their wives, and Clara had a separate turkey dinner. Following the feast, a joy ride was arranged.

After dinner the horses were brought up and the ambulances manned or womaned or both, and off we started on a voyage of discovery over the island, the main road of which leads directly to the Beaufort ferry a most splendid Island it is[;] our ride lasted till dark – we gathered autumn leaves and keepsakes of all kinds and returned to camp laden, then I called for my carriage and came home by moonlight across the bay as smooth as a piece of glass.

Walt Whitman also had left Washington. He spent Thanksgiving of 1863 in New York City. His friend Ellen O’Connor heard he would be returning home and reached out to him on November 24.

How I long to see you. Are you going to be here by Thursday, Thanksgiving? I wish I knew, for I would get a good big turkey and we would have a jolly time.

The day before the holiday, November 25, Whitman visited wounded soldiers at Central Park Hospital. He found it to be “a well-managed institution.”

In 1863, President Abraham Lincoln gave Americans across the country a reason to celebrate amidst the terrible suffering of the Civil War. Like the Pilgrims before them, people needed a reminder that there were good things in their lives to be thankful for. The holiday of Thanksgiving today still gives everyone the opportunity to examine their blessings and to be thankful for them, despite whatever tough times we may be going through.

About the Author

Roy Blumenfeld is a history enthusiast and volunteer docent at the Clara Barton Missing Soldiers Office Museum. He holds a BS in Political Science from Appalachian State University.

Sources

Websites

- “They Gave Us Our Thanksgiving.” The Midlands Journal, 17 Nov. 1933. Library of Congress,https://www.loc.gov/resource/sn89060136/1933-11-17/ed-1/?sp=6&r=0.105,0.058,1.097,1.73,0

- “Day of Thanksgiving.” Daily National Intelligencer, 26 Nov. 1863. Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/resource/sn83026172/1863-11-26/ed-1/?sp=3&q=Thanksgiving&r=-0.012,-0.287,1.03,1.624,0

- “Thanksgiving Proclamation, 1863.” Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, n.d., https://www.gilderlehrman.org/history-resources/spotlight-primary-source/thanksgiving-proclamation-1863

- “Proclamation 147.” The American Presidency Project, n.d.,

https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/proclamation-147-thanksgiving-day-1865

- “Julia Wilbur Diary, 1863.” Haverford College & Alexandria Archeology,

https://media.alexandriava.gov/docs-archives/historic/info/civilwar/juliawilburdiary1863.pdf

- “Ellen M. O’Connor to Walt Whitman, 24 November 1863.” The Walt Whitman Archive, n.d., https://whitmanarchive.org/item/loc.00942

Books

- Stearns, Amanda Akin. The Lady Nurse of Ward E. The Baker & Taylor Company, 1909.

- Oates, Stephen B. Woman of Valor: Clara Barton and the Civil War. Kent State University Press, 1996.

- Lowenfels, Walter. Walt Whitman’s Civil War. De Capo Press, 1989.