Relics of Andersonville

By Mrs. Frances D. Gage

February 28, 1866

In a small room on the third floor of a building in Washington, D.C., I sit me down to write this letter. No mirrors flash back light or beauty from these walls; no Vandykes, Raphaels or Reubens create envy in the bosom of the passer by. Its plain, cheap carpet, its chairs, its tables—for use, not ornament—wear no gorgeous coverings, but bear the burdens of days of toil and nights of watching and weariness, in the form of ledgers, and boxes filled with documents, that have been the coinage, every one of them, of aching hearts.

Yonder, in the corner, is a cabinet. A few plain board shelves are set against the wall, containing the most unique, priceless treasures in the world. No costly gems glitter there; no exquisite shells from the depths of the sea entrance with their splendor of color and form; no birds with gaudy plummage remind us of nature’s magnificence in some far-off isle of the ocean. Nay, none of that! O, pen of mine, write quietly! O, eyes, but back your tears! Cease throbbing heart, your painful pulsations while I tell the story as best I can.

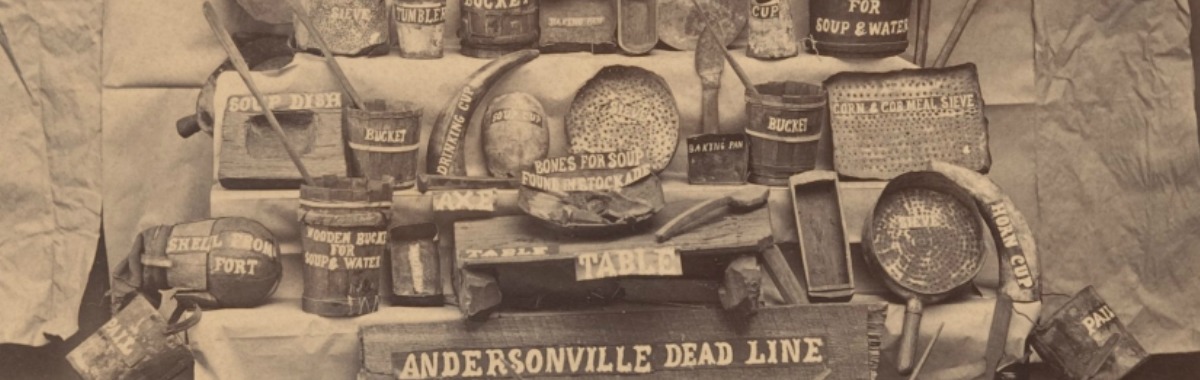

Come nearer; let us look at these things. The bits of tin, perforated with holes, were once bottoms and sides of canteens, or oyster cans, grown old and rusty with use, gathered up by weary hands, and pierced by nails to make sieves through which to pass the meal made of corn, “ground cobb and all,” which formed the rations of our soldier prisoners at Andersonville.

These rusty oyster cans, with a bail of old wire rudely adjusted, were the kettles in which they gathered the bones, and reboiled them to make soup. These paddles, soiled and grim at the handles and scoured at the base with constant use, stirred the coarse meal and water together into mush for starving men. Those splits of wood, woven together like chair-bottoms, were the plates they used.

See you these little wooden troughs whittled with a jack-knife, rough, tiny, some not holding a half-pint? They held the meagre mean when cooked. These are the spoons of wood that conveyed the loathsome food to their famished lips.—Those cows’ horns, wrought into drinking cups; these little tubs of chips of wood, hooped about with tow strings, served the same purpose. One oyster can, for which no bail could be found, has a strip of tin cut from the top with short, narrow bits for hinges, and thus, as a kettle for cooking, was made to do its noble service.

These bits of board! Some careless untaught eye might take them for kindling-wood. As I write, I ask myself, is the theory that spirits of the dead linger around the scenes of joy or sorrow that they knew in this life, a true one? If so, how many thousands are looking down this night at the thoughts I am tracing with my pen! Those bits of scantling, broken, unplaned, five inches wide, and two or three feet long, are fragments of the “dead-line” at Andersonville. He who, starved, maddened, reckless, preferred death to continual torture, had but to pass this brittle boundary to be ushered instantly into the presence of Him who has said, “Vengeance is mine, I will repay.”

Turn this way. That board, leaning in the corner, with its black figures, “7,606” at the top is the head board which Wirz—he has gone to his account, I will use adjectives with his named, suffered to be placed where one dear and nearly akin to her who gathered these relics, was laid away in that vast cemetery of murdered men.

7,606! Can you realize it? Seven thousand six hundred and six prisoners, who, starved, scorched in the burning sun, maddened, hopeless, prayed for death and found in their shallow graves surcease from anguish! And 7,606 is scarce half. On, on, on—up, up, up go numbers to 12,920 that have been found, recognized, and marked. O! God of mercy is there, can there be produced such another record of the results of slavery at this!

But let us look further. These bayonets were picked up in that Golgotha, and this letter-box, into which thousands, ay, tens of thousands of letters were dropped, but never one went out to gladden the oppressed hearts of friends! Perhaps no five pieces of timber were ever nailed together, that have enclosed so many tales of distress, or so few of happiness or joy, as theses.

This is the worn-out stump of a hickory broom, with which the skeleton hands tried to keep clean; this is a ball from one of the many guns that were mounted on the seven forts surrounding the prison. A paroled prisoner asked Wirz one day:

“What will you do with us if Sherman’s army comes to the rescue?”

“By tam! I puts you in the stockade. I turn de guns on you, and blow de brains out of every tam one.”

But let me stay this fearful record, and tell how these things came to be here in Washington. Miss Clara Barton, in whose little parlor I find them, brought them with her on her return from here expedition to Andersonville, where she went by request of Secretary Stanton, in company with Capt. James M. Moore, A.Q.M., to enclose the grounds of the Andersonville cemetery, and identify the graves and mark them with headboards, which expedition was inaugurated, at her request, by the heads of the department.

“I gathered these things up,” said Miss Barton to me, “and was told their uses at the places where I found them. I brought out some from the deep burrows our men had made—those caves dug out by their weak hands to shelter them from burning heats and chilling dews, and into which many crept, never to emerge again, til their fellows bore them to their last resting-place.”

Was I wrong in saying her cabinet contained the most unique and priceless treasures in the world? Many a mother, wife, or sister would gladly exchange her gold and jewels for those records of the last days of some loving heart, so frightfully stilled. One lady, looking at them with tears coursing down her cheeks, exclaimed, “I would exchange my diamonds for “these.”

“Your diamonds could not buy them,” was the answer of the heroic woman who has done so much to ease the sorrow of a nation.

As I said, these tables bear the burdens of aching hearts. Six thousand letters from bereaved friends, who have asked her to help them find their missing dead! And still they come! Still the mother cries out in anguish and suspense, “What has become of my boy?” Still the wife pleads to know of him who was her all, whom she gave to her country to die for it, if need be; but not to be lost uncared for, and unsought. One hundred letters a day often lay upon Miss Barton’s table, every one frightened with sorrow.

Do you wonder I sit in awe in this almost sublime room? Do you wonder that I ask, “Is the theory true that spirits can linger near mortals upon earth?” If so, will they not bear near be near breathing over this kind, gentle woman, to help her in her benevolent work? Do they not long to have those they loved, and who still wander in life asking them, let into secrets of their fate?

Six thousand letters? Some of them giving the names of twelve or fifteen missing men, and each requiring an answer to the individual who wrote it; and five, ten, twenty, thirty, even seventy-five letters of inquiry to gain the information needed to reply to its queries.

Some of you who read this have, perhaps, seen Miss Barton’s “Roll of Missing Men,” and her request appended to that “roll” for information. You may suppose those names are all she has gathered, and wonder that she has no more. You imagine she has gone to the quartermaster’s department or muster roll for that number. Let it be known that every name on the list has been taken from some letters of friends, which is now on file in her possession, asking for the missing. Most of these letters are from women, either in their own handwriting or that of an agent, telling their own story of loss and sorrow.

Her “roll” was printed in June or July, and copies scattered all over the country. It contains but three thousand names. There are many more that are now waiting to be put in shape and that will be printed as soon as possible.

This is a great work, requiring many hands, and hard, steady labor. Friends must be patient, thankful for what has been done, and trusting for the future.—While Clara Barton lives and can work, she will not forget the widow in her affliction, or let the fatherless ask in vain, or disappoint the mother’s hope—if it is possible to do otherwise.

One thing more. Let it be ever understood this is a private enterprise, begun and wholly sustained by Miss Barton. She receives no salary from any department of Government, or association of the people, and is responsible to the people only through her promise to do this work. –Independent.

The following article is copied from an original in the Library of Congress.

A photograph and an illustration of the relics described are also available.