Kӓthe Kollwitz

Amelia Grabowski

Grief carved in stone. Kӓthe Kollwitz captured this in her artwork, particularly in the two memorial statues she created to honor her son Peter, who died during World War I.

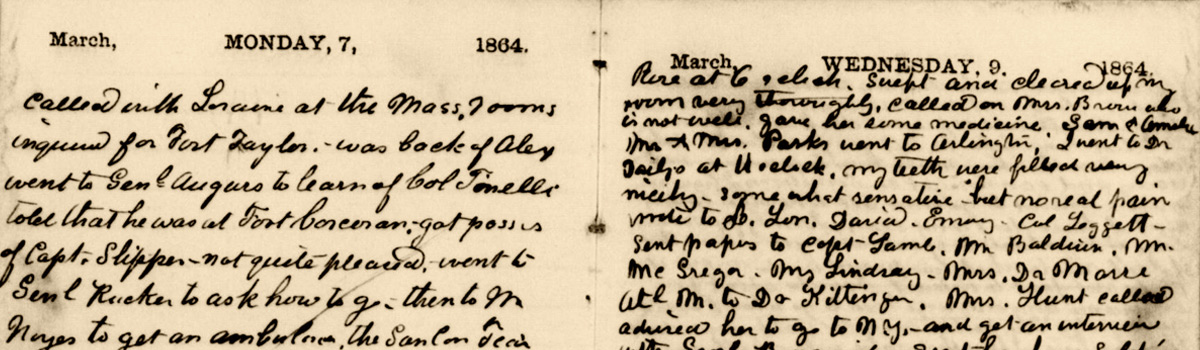

The Mothers, Courtesy of MOMA

Kollwitz was a German Expressionist artist whose principle medium was lithographs, although she did create some sculptures. She grew up surrounded by wars and death, and did not shy away from those themes in her artwork. She created print series about both the German Peasant’s War and World War I. As previously mentioned, Kollwitz’s younger son, Peter, died outside of Belgium in World War I. Peter’s death drove much of Kollwitz’s later artwork and her pacifist political sentiment.

Pieta

Revisiting Kollwitz’s war works for this blog post, what strikes me is how the bodies interact with one another. In some of the works, like Pietà or The Mothers, the bodies cling each other tightly until they become a singular unite. In the case of the Pietà, which features a mother holding her dead son, this is easy to understand. In The Mothers and other works, we see people brought together, united by the grief, and clinging to each other for support.

Grieving Parents

However, the uniting power of grief certainly isn’t the rule for Kollwitz’s artwork. In Grieving Parents, one of the memorial statues that she created in honor of Peter’s memory, the parents are not only physically separate, they appear psychologically separate as well—each caught up in their own world of grief, unconcerned with the other.

The contrast between the togetherness of the The Mothers and the division of Grieving Parents got me wondering if unity in grief was a privilege—obviously a privilege that no one wants to be in the position to have, but a privilege nonetheless. The family and friends who lost a loved one in the Civil War certainly would have been able to find others nearby with similar experiences. Regiments were often organized geographically, therefore it was possible for a large portion (if not all) of a town’s young men to be killed in one battle. Did sharing the grief with one’s community make it any easier to bear?

One thing is for sure, many Civil War parents would have yearned for physical togetherness wit the deceased—the privilege to hold their loved ones again, as the mother does in the Pietà. For many, this was impossible. If the location of your loved one’s corpse was known, embalming the body for travel and shipping it home frequently proved too great an expense for the family to afford. For many, the “final disposition” of their loved ones remained unknown: had they died in battle, in a hospital, were they a prisoner of war? After the War, Clara Barton would search for over 60,000 of these missing men.

About the Author

Amelia Grabowski is the Outreach and Education Coordinator at the National Museum of Civil War Medicine and the Clara Barton Missing Soldiers Office Museum.

Tags: Art and War, Kathe Kollwitz, Lithograph, Sculpture, World War I Posted in: Art and War